How the COVID-19 Pandemic Exacerbates Inequality in the United States

“Essential workers.” “First responders.” The COVID-19 pandemic brings new pictures to mind when these phrases are used: doctors and nurses and orderlies in hospitals; all the hospital crews who clean the rooms and the equipment and wash the sheets and towels and scrubs, the hospital cafeteria workers who feed both patients and workers.

But the list of first responders goes far beyond the medical field, too. Transportation workers, from bus and subway drivers to taxi and ride-share drivers, deliver both medical workers and their patients to hospitals. Behind all of these workers are all those who work to sustain them. Another long line of essential workers runs from grocery store cashiers and stockers back to truck drivers delivering the food given to them by warehouse workers.

That food, in turn, comes from processing plants of various kinds, often filled with hundreds of workers standing shoulder-to-shoulder for long shifts. Furthermore, the food being processed has already passed through the hands of various farmworkers, without whom we would not have food to eat. Similar workers stand behind all the other items we all need to survive this pandemic: paper products (more tp!), masks and gloves, cleaning products, etc.

All of these essential workers and first responders also need other workers to support their social reproduction: take-out restaurant workers to feed them, childcare workers to tend their children, elder-care workers to watch over their parents.

These essential workers have been praised throughout the media now and for the past two months. However, on May 1st, International Workers Day, we need to be concerned about two things: what is happening to these workers now and what will happen to them after the pandemic subsides.

What do all of these essential workers and first responders have in common? Unlike the “home front” workers of past wars, who tended to be groups dominated by white men, the essential workers of this pandemic include many more women, people of color, and immigrants (many of them undocumented). These are groups that have historically experienced lower wage levels and lower levels of power in their workplaces. In other words, individuals who have formed the lower levels of our income structure and our societal structure make up the core of “essential” workers.

Many of us have been talking about rising inequality in the U.S. for years already. The coronavirus pandemic increases that inequality. In New York City, the Department of Health reported that as of April 6, Latinx individuals made up 33.5% and Blacks made up 27.5% of COVID19 deaths.[1] Both Detroit and Chicago have reported similar imbalances in death rates across race and ethnicity.

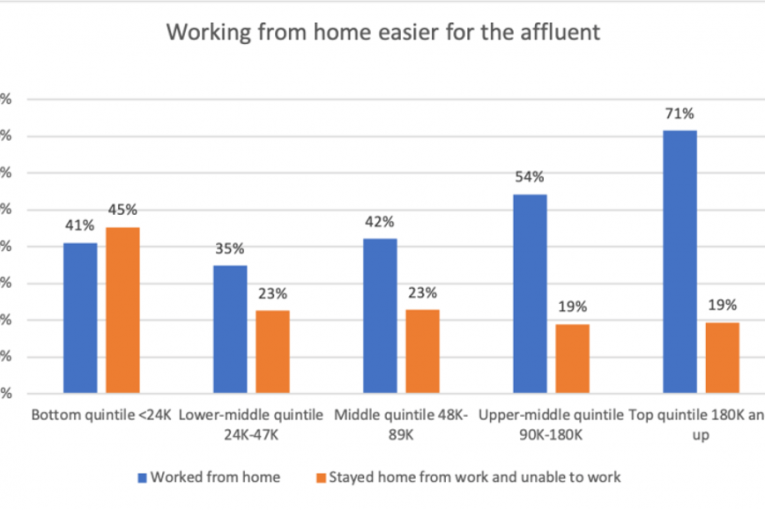

A study by the Brookings Institute at the end of March examined information from the March 16-22 Gallup Poll in order to examine the growing class divides in this time of the COVID-19 pandemic.[2] The table reproduced below demonstrates how starkly different the experiences of workers earning over $180,000 and those earning less than $24,000 are. While 71% from the first group were working at home during the third week in March, only 41% of the lower-income group could do so, while 45% of that group found themselves unemployed. This finding is not all that surprising: even before COVID-19, those with higher incomes and education were far more likely to be working at home.[3] COVID-19 merely highlights this disparity.

Figure 5:

Source: Sample of 8572 randomly selected adults from the Gallup Panel, interviewed over the phone from March 16 to March 22, 2020. BROOKINGS

Missing from this chart are all those essential workers described above, who must work and do not have the option of working from home. These essential workers fill in the rest of the chart, particularly for the middle-income quintiles: 42% of those earning $24-47,000; 35% of those earning $48-89,000; and 27% of those earning $90-$180,000 could not stay at home in late March.[1] These are the workers facing COVID-19 most directly. “Sheltering in place” means very different things for those at different points of the income scale.

Perhaps, after the pandemic finally subsides, we will all remember these essential workers and recognize these workers’ value to our society. If we succeed in doing this, the resulting security and higher wages for such workers will help propel the nation’s economic recovery. If the opposite happens and we return to de-valuing the workers now celebrated as the “front-line” of the pandemic, our country will continue on its path to even greater economic inequality. That would be a shame. On International Workers Day, let us remember the imperative to honor concretely and substantially our front-line essential workers both in the midst of the pandemic and after the pandemic slows.

Ileen A. DeVault

Academic Director, The Worker Institute

Professor of Labor History, ILR School, Cornell University

This piece highlights just a few of the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating inequality in the United States. Future contributions from other Worker Institute colleagues will address in more detail these and other aspects of inequality and the pandemic. If you want to contribute something to our discussion, please email Ileen DeVault, iad1@cornell.edu.

[1] Note that only 10% of those in the upper income quintile (over $180,000) worked outside the home, giving them that much, at least, in common with the lowest income quintile (under $24,000) only 14% of whom continued to work outside their homes.

[1] April 6: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-deaths-race-ethnicity-04082020-1.pdf April 16: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-deaths-race-ethnicity-04162020-1.pdf

[2] Richard Reeves and Jonathan Rothwell, “Class and COVID: How the less affluent face double risks,” https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/03/27/class-and-covid-how-the-less-affluent-face-double-risks/ URL 4/21/2020]

[3] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Job Flexibilities and Work Schedules—2017-2018: Data from the American Time Use Survey.” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/flex2.t01.htm URL 4/21/2020