For Kids’ Sake

All kids run a temperature from time to time. But as a pediatrician, Zoltan Antal, MD, is well aware that detecting fevers in young children can be tricky—and vitally important. That’s why the topic was a key part of a pediatric healthcare workshop he taught in Manhattan’s Washington Heights neighborhood one Saturday afternoon in March. “How do you check for a fever?” he asked the nine students, all women currently working as nannies or trying to enter the field. Several responded that they would first press a hand to a child’s forehead to see if he or she feels hot. “Many people do that,” Antal said with a smile.

But as he went on to explain, children can still be sick when they don’t seem warm. Plus, he noted, in infants even a slight fever can be a sign of a potentially serious infection, and keeping a careful watch is imperative. Antal encouraged the women to use a thermometer to ascertain a child’s temperature, adding that popular models placed in the ear may not give an accurate reading in newborns. The gold standard, he said, is a rectal temperature, acknowledging that it can be difficult to get a child to cooperate—and at that, the women all laughed and nodded. Antal then suggested certain techniques—like putting a baby belly-down across your lap¬—to make the process easier. For Melquisedec Mejia, who cares for an infant with a heart condition, this was valuable information. “I have to take his temperature a lot,” she said, “and now I know I have to take it differently.”

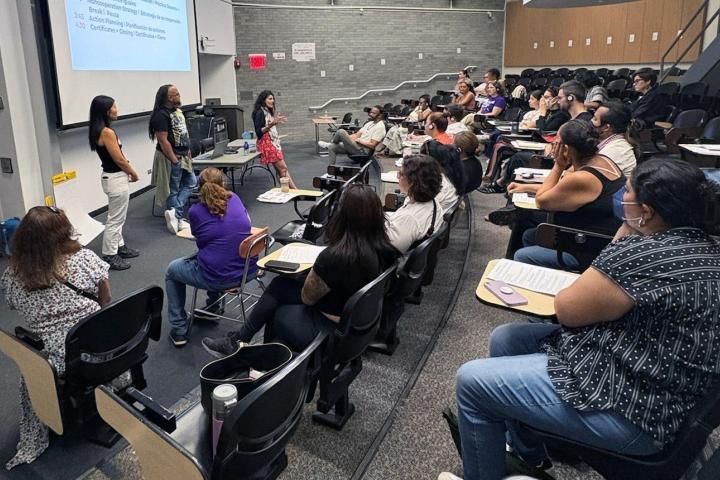

For those attending that day, Antal’s pediatric workshop was the last of seven they had to take to complete a thirty-five-hour training program developed by Cornell Cooperative Extension and the Worker Institute at Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, in collaboration with Weill Cornell Medicine and the National Domestic Worker Alliance. Intended to improve skills among childcare providers in New York City and Westchester County, the program also covers such subject areas as CPR, nutrition, social-emotional development, workers’ rights, and guidance on how nannies can effectively communicate with parents. Such training, organizers say, can benefit not only the nannies but the youngsters they nurture and the children’s families. “Caregivers are often the first to identify a problem, sometimes even before a child’s parents,” says Antal, an associate professor of clinical pediatrics and chief of pediatric endocrinology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell. “They are on the front lines every day.”

According to its organizers, the program is aimed to enhance the quality of services that nannies provide and boost their chances of being hired, while raising industry standards and elevating the value of an occupation that is frequently underappreciated and underpaid. More than 350 participants have graduated so far, each earning a professional development certificate from Cornell’s ILR school. In a recent survey of program alumni—most in their thirties and forties, nearly all from underrepresented groups—63 percent felt the training was a strong factor in helping them secure and retain jobs. Three-quarters reported that the program had a positive impact on wages, and 79 percent said it had a positive effect on relationships with employers. The majority also said that they use the medical, nutrition, and child development knowledge gained during their training “frequently” or “all the time.” “Hopefully, having this kind of education helps their ability to take care of children,” says Antal, “but it also gives them the opportunity to get better jobs or work in them more confidently.”

Antal has been involved with the program since 2011, when he volunteered to create its pediatric health curriculum—which also covers such topics as the best ways to spot common illnesses, what to do if a child sustains a head injury or swallows a poisonous substance, and how to use an EpiPen in the case of a severe allergic reaction. Once a month, he travels to various organizations for domestic workers around the city that offer the training—such as Adhikaar, a social justice nonprofit based in Woodside, Queens, that advocates for the Nepali-speaking population, and Beyond Care, a childcare services cooperative in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, whose members are mostly Latina. Course fees vary according to each organization, and some offer the program as a free benefit to members. Interest has increased so much that Antal is helping train two registered nurses and an MD from a community health center who will eventually take over some pediatric classes; nannies who already have their certificates are also being coached as peer educators on other topics. “There’s been this wonderful ripple effect,” says Antal.

Classes are largely held in areas with a high concentration of immigrants from the Caribbean, Asia, and Latin America; in cases where English is a second language, an interpreter is always present. For instance, for Antal’s session in Washington Heights—at a class hosted by NannyBee, a nanny-owned childcare service in Upper Manhattan that offers the training for free—Antal conveyed his expertise in English, which was interpreted into Spanish for the nannies, who eagerly asked questions and shared opinions. Participants like Mejia, who came to the U.S. nine years ago from Honduras, say the training has already opened doors. Before landing two part-time nanny positions earlier this year, Mejia worked as a waitress—but, she says, “I feel like I have more opportunities now.”

Rose Maria Peña, who completed the program last year and is now a nanny for two boys under five, agrees. She was a schoolteacher in the Dominican Republic before moving to the U.S. in 2016. In New York City, she worked as a home health aide for the elderly, but didn’t find it as satisfying. She learned about the training workshops at an English class and immediately signed up; NannyBee helped Peña get her current childcare positions while she finished the coursework. “I feel as though I’ve regained my life,” she says of working with kids. “I feel so happy and completely renewed.”

For Antal, the program’s mission is close to his heart. His family came to the U.S. from Romania when he was nine, and his mother worked as a child caregiver to make ends meet. “Her employers didn’t take good care of her,” he says. “They demanded a lot and she didn’t know her rights. But at that point, she just wanted a job.” When Antal first began with the program, he says, “I came away thinking, this is fantastic. It’s helping people just like my family improve their lives.”

— This story was written by Heather Salerno and originally appeared in Summer 2019 issue of The Magazine of Weill Cornell Medicine