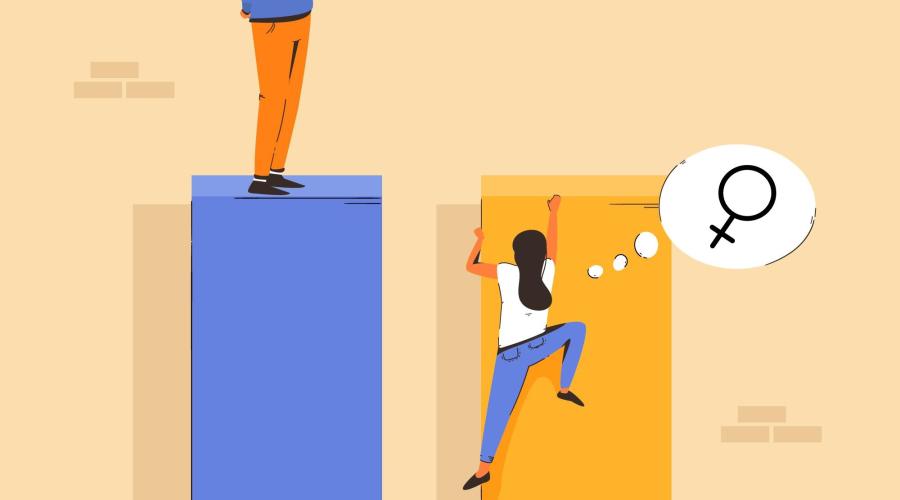

Pay remains stubbornly attuned to gender. What to do?

Interventions have shown success to address this persistent pay issue

Intro: What is the Gender Pay Gap?

The classic definition of the gender pay gap is the average difference in earnings between men and women in the workforce. The fact that women earn less than men is repeatedly touted in the media – particularly on “Equal Pay Day” .

The definition conjures images of a woman and a man doing the same job, but the woman earns less. Researchers have studied this problem in depth and the evidence is eloquently summarized in a 2023 report by the Pew Research Center. While overt discrimination is sometimes the case, the gender gap more often arises from women and men choosing different jobs and female jobs paying less than male jobs, women working fewer hours than men in the same jobs, and women leaving paid employment for periods of time for caregiving responsibilities and thus lowering their earning potential. In other words, there are obvious factors that explain differences in earnings between men and women.

The good news is that progress has been made. A key finding from decades of research is that the pay gap narrowed steadily from the 1960s to the 1990s. Jobs are less strictly gendered. Men have entered traditionally female occupations such as teaching and nursing and women have entered traditionally male occupations such as engineering and management. Companies are less likely to discriminate as legal repercussions have become more dire. Although gender-based pay differences were historically driven by discrimination, gender stereotypes, and occupational sorting, this explanation no longer holds.

When talking about the gender pay gap, it is important to understand the difference between adjusted and unadjusted differences. The unadjusted gender pay gap is a straightforward comparison of the average earnings of all men in the workforce versus the average earnings of all women in the workforce, without considering any other factors. So, when we hear that women earn 84 cents for every dollar men make, it usually implies an unadjusted pay difference. Meanwhile, the adjusted gender pay gap takes into account various factors that can influence earnings, such as education, occupation, years of experience, hours worked per week, industry, and location. If after controlling for these factors, there is still a difference in pay, then one might assume that it is an adjusted gender pay inequity.

Unfortunately, progress in narrowing both adjusted and unadjusted gender pay gap has stalled. Women still earn less than men in absolute numbers. Even more so, Blau and Kahn found that in 2010, traditional factors like education and work experience accounted for only a small portion of the gender wage gap due to the reversal of the gender differences in education and significant reduction in the gender experience gap. Instead, differences in occupation and industry distribution remained significant contributors to the gap. This progress slowed down after 1989, especially for highly skilled and executive-level workers where men still had an advantage compared to women.

What is Behind the Current Pay Gap between Men and Women?

Over time there has been a lot of effort put into closing the pay gap between men and women but the problem remains. The question is why.

Claudia Goldin, the 2023 Economic Sciences Nobel Prize winner, offers an answer. Goldin argues that the main culprit is the structure of work and compensation. She demonstrates that pay is not a linear function of the number of hours worked. Instead, overtime is compensated at a higher premium. While this has long been true for hourly workers who earn a 1.5x or 2x overtime premium, the premium is much higher in high-paying occupations. This is surprising because we typically think of high-paying occupations – doctor, lawyer, consultant – as salaried positions. How are these workers earning an overtime premium? Goldin argues that the returns to overwork arise because people are promoted more quickly, are recruited to firms that have higher work hour demands but also pay much more, and have the market power to command higher wages based on their accrued experience and expertise. This is a different kind of “sorting” that explains the gender pay gap. Here men and women have the same educational credentials and the same nominal job, but the pay gap arises from differences across firms. Thus the gender pay gap persists despite women entering higher paying jobs and being willing to put in the same amount of effort and time as men to attain the positions.

The highest paying firms demand that employees be flexible and constantly available. Unfortunately, this has been shown to be significantly more challenging for women, as they continue to bear the primary responsibility for the majority of household chores and caregiving duties. [Goldin and Pew Research Center]

So, Goldin’s main points are that overtime work is prevalent in high-paying occupations and that women continue to assume the primary responsibility for managing households. These factors, together, lead to women having fewer opportunities to engage in overtime work and thereby reap the benefits of high-paying jobs. Thus, this helps to explain some of the persistent pay gap between men and women, even in the absence of overt discrimination.

While employers have no control over the household division of labor of their employees, what could they do to close the gap?

Recommendations: What Can Be Done Differently?

Closing the gender-based pay gap is a multi-step process that requires the involvement of various parties. While governments can tackle the problem from the policy perspective, companies can make a positive contribution and lead by example in solving the pay inequity problem.

Track the Issue

The first thing that companies should do is to start tracking the pay parity between their male and female employees. According to Just Capital’s 2023 study of the Russell 1000 companies, only 32% (or 302 companies) disclose that they conduct a gender pay gap analysis. While it is still a small number, the study acknowledges the positive trend when compared to previous years, increasingly more companies conduct a pay inequity evaluation. Moreover, when conducting a gender pay gap analysis, it is crucial to look at the adjusted pay differences by controlling for various factors that can affect differences in pay like occupation, education, etc. Interestingly, only 130 companies calculate the adjusted pay gap.

Disclose the Results

The next step is for companies to publicly disclose the pay parity index. By doing so, companies will be able to take accountability for addressing the gender pay gap issue, especially when the pay is not equitable among their employees.

While 32% of companies disclose that they track their gender-based pay equity situation, only 14% (or 130 companies) publicly report the results. Interestingly, among those companies that chose to disclose their results, all reported figures are close to gender pay equity. One might assume that the decision to disclose the figures depends on how well the company is doing in terms of paying its employees fairly. Alternatively, it can simply indicate that companies, which report their results, have done their job in closing the gap in the first place.

Close the Gap

While it is important to track and report the information on the gender pay gap, it is also crucial to make a positive change. Among 14% (or 130) of companies that disclose the pay information, only 42 report pay equity between their male and female employees. Therefore, the next step is for companies to close the observable gap in workers’ compensation, once it has been identified.

In the meantime, companies that offer their employees an equal pay for equal work might try to close the gender pay gap even further. They can re-evaluate the job demands, especially for higher-paying positions and see if both men and women have equal access to career opportunities.

Furthermore, they can help all employees recognize the shared responsibility of housework and caregiving. One of the ways companies can promote it is by providing their employees with negotiation and interpersonal skills training that can be deployed both at work and at home. During these trainings, employees can learn how to negotiate better career opportunities at work and more equal division of housework at home.