Healthcare Insights: Primary Care Crisis: What To Do?

By John August

On November 5, 2025, 600 primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants staged a one-day strike at Allina Health in the Twin Cities of Minnesota and locations in northwest Wisconsin. It is the first strike on such a large scale by private sector doctors and allied professionals.

Negotiations have been underway for more than 20 months for a first collective bargaining agreement. The primary care group voted to be represented by Doctors Council SEIU in October of 2023.

In the above articles about the strike and the organizing campaign, you will read about the issues that drove the group to unionize: burnout, understaffing, and low pay and benefits.

I will keep close watch on the progress of negotiations and continue to report on the outcomes.

In this month’s Healthcare Insights, I want to discuss some of the root causes of what is a very deep crisis in primary care across the country, root causes that are reflected in the labor dispute at Allina Health. The fact that physicians organized a union and have gone so far as to strike indicates a passionate desire for collective voice and action that is deeper than any time before.

This dispute also raises important questions about the relationship of traditional organizing and collective bargaining and how and whether or not the root causes of the issues can be resolved.

What is Primary Care and Why Is It So Important?

Primary care is a catch-all term for the kinds of care that nearly everyone needs or will need in their lifetime: pediatrics, family medicine, internal medicine, and geriatrics. Primary care is the gateway to preventive care, management of chronic conditions, and treatment of what appear to be minor illnesses and injuries which if left untreated, can lead to more complex health problems. Primary care is where we get relief from respiratory and ear infections, where we get our vaccines, where we take our kids for check-ups.

Without primary care access, anxiety is heightened as unnecessary suffering goes unresolved.

“Primary care is a fundamental part of the nation’s healthcare system. Better access to and use of primary care has been shown to improve treatment of chronic conditions and increase life expectancy. However, it is well-documented that significant challenges face the workforce providing this care. These include shortages and maldistribution of primary care providers (PCPs), low compensation compared to other health occupations, increasing burnout and job dissatisfaction, and an aging workforce.”

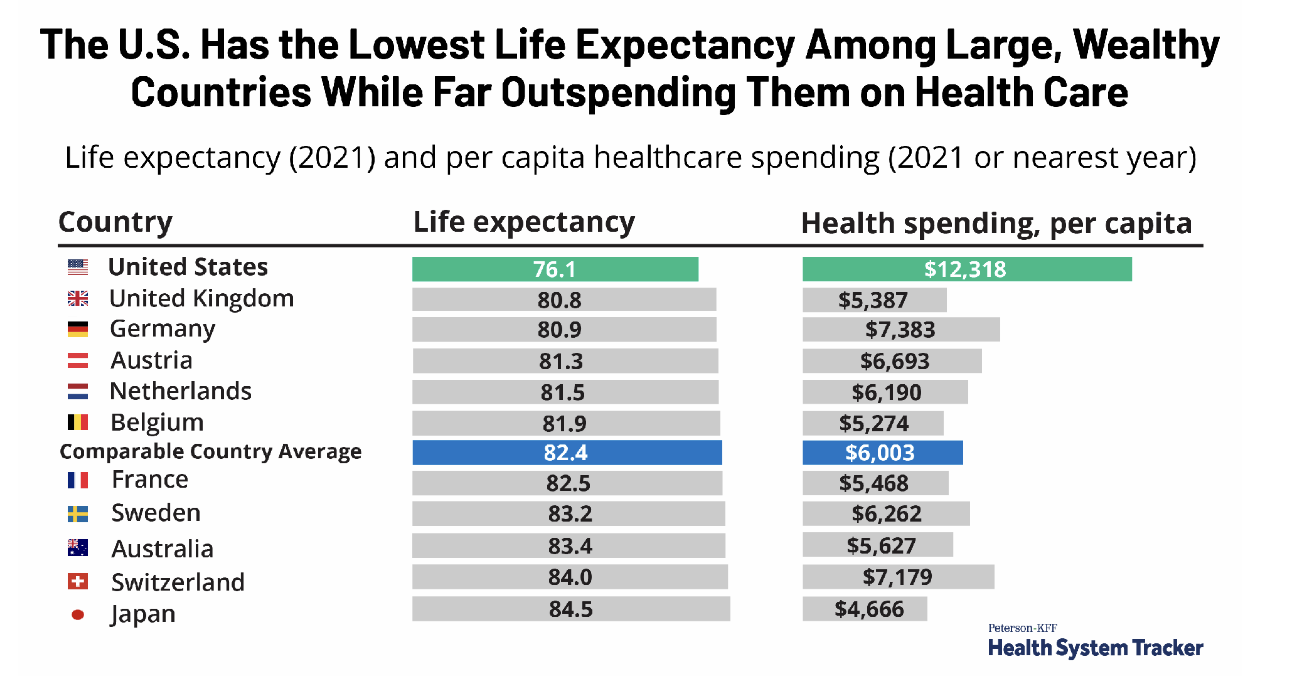

As cited above, a key determinant of the nation’s health is life expectancy. The below graph illustrates that among wealthy nations, the U.S. has the lowest life expectancy by far, while spending the most overall on healthcare. Only 5% of that spending is on primary care.

Underlying causes of the Primary Care Crisis

- Financing: Declining investment and fee-for-service payment are hindering primary care clinicians’ ability to meet growing patient needs.

- Workforce/Access: Insufficient funding is diminishing the primary care workforce and access to care.

- Training: Misdirected graduate medical education funding is not producing enough new primary care physicians, exacerbating access issues for patients.

- The disparity in growth in medical residents per capita between primary care and all other specialties

- Technology: The lack of investment in Electronic Health Records has led to burdensome systems that drain clinicians’ time, thereby reducing patient access to care.

- Research: The lack of research dollars to study the practice of primary care is limiting evidence-based improvements in care.

“The fragility of primary care remains rooted in the lack of tangible progress on financing — specifically, how and how much primary care practices are paid. Yet, policy shifts at both federal and state levels have the potential to drive significant change in the years ahead. “

How Did We Get Here?

In an extraordinary recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine, we learn that the crisis in primary care is in truth a choice that the nation has made!

“Despite accounting for about 35% of all U.S. health care visits, primary care receives less than 5% of health care resources. Yet experts have been calling for greater investment for decades. Indeed, while the number-one recommendation of the most recent report on primary care from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine was greater investment, the report’s most striking feature was the committee’s explicit task: create an implementation strategy for recommendations that were similar to those made 25 years earlier but largely ignored. The great mystery of primary care, then, isn’t how to

make it better, but why we’ve chosen not to.”

One popular idea to try to solve the primary care crisis has been to make medical education free or much less costly. The theory goes that this would reduce or even eliminate the high debt burden that medical education creates for students. If medical residents had little to no debt, it was thought that they would be more apt to choose the less lucrative specialties to train for such as the primary care specialties.

NYU Medical School was one of a number of medical schools that offered free tuition. Nonetheless, in 2024, only 14% of graduates chose primary care specialties, less than half the proportion of currently practicing U.S. physicians who are Primary Care physicians. This rather shocking outcome is due to the fact that primary care is a “no-win” specialty and is regarded at the “bottom of the medical hierarchy”. As such, even with lower medical debt, medical graduates are not going into the primary care fields.

Can Collective Bargaining Solve this Crisis?

The recent strike by primary physicians and advanced practice professionals at Allina Health is described as a dispute over burnout, understaffing, and low pay, all issues closely identified with the national crisis faced by primary care doctors. Yet, the collective bargaining process there has included 20 months of slow and acrimonious traditional bargaining. While the issues are clear, the solutions will not rest in a final collective bargaining agreement (CBA) in as much as it is clear that the external forces of financing and medical hierarchies will remain. A CBA will bring voice and protections to the primary care workforce at Allina. This is indeed great progress. It would also appear that the underlying causes of the problems of understaffing, burnout, and low pay will linger, and will likely drive further disputes as both primary care providers and patients will remain underserved.

What if physician organizing and collective bargaining efforts began and were sustained with a different approach?

What if physician concerns were framed in the context of root causes and external forces that impact the community, the health system, and the doctors as a shared experience and reality?

What if the unionization process did not follow the traditional rules of bargaining unit by bargaining unit recognition campaigns, but started from the premise that all doctors in a system regardless of traditional bargaining unit rules were set aside; or what if campaigns involved doctors across health system boundaries, and defined the campaign as one on behalf of an entire community?

What if bargaining advanced the premise of shared purpose and shared interests for the community as a whole, including patients, providers, and health systems? What if bargaining incorporated a new framing of dialogue that included all these sectors to work together to resolve the underlying barriers to improved primary care access and quality?

A New Approach: Disruption, Jurisdiction Shifting, and Changing Branches of Government

Professors Kate Andrias of Columbia Law School and Ben Sachs of Harvard Law School have written extensively on the topic of the essentiality of new approaches to unionization and the attainment of power for poor and working-class people. They recognize the need for labor law reform so that workers can achieve power to end severe income inequality and lack of social improvement for the tens of millions of Americans who struggle to survive while working for low wages and poor working conditions.

They also recognize the “chicken-and-egg dilemma”, which is that there has been no significant labor law reform in the U.S. for 90 years, and as the labor movement has gotten weaker, its ability to achieve labor law reform has been impossible. In other words, without the power to achieve reform (the chicken), there can be no reform (the egg).

Their idea is that there is no time to wait. Furthermore, that by significantly breaking from traditional organizing and bargaining (one bargaining unit at a time, one contract at a time), workers can organize successfully, but on a different set of premises: the creation of social movement.

The crisis in primary care makes a great case for a focused social movement. It involves hundreds of thousand of health care professionals, whole communities, and the need to fundamentally change government financing:

“A social movement may lack sufficient political influence to ensure enactment of organizing-enabling legislation through ordinary political advocacy but may nonetheless possess sufficient disruptive power to secure enactment in the form of legislative concessions meant to restore social order”. (Andrias and Sachs)

What if organizing primary care doctors and allied professionals took this approach? And what is stopping them from doing so?

What if the disruptive power described as necessary to provoke governmental intervention were grounded in a shared strategy by providers, community, and health systems?

These are questions that ought to be taken up? If there is to be disruption, let it be a disruption of a system that is dysfunctional, spends resources improperly, discourages an engaged and sustained workforce, and results in harm and ill health.

Collective bargaining can be redefined as social dialogue: a new form of bargaining among traditional adversaries who have determined that their common interests override their traditional opposition to one another.

It seems that the time is right.

Doctors are organizing and bargaining.

The traditional professional organizations of doctors, including the American Medical Association, the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, and many state medical societies have all called for collective action by doctors with support for collective bargaining. In so doing, they also discourage strikes and adversarialism. These organizations and their potential allies, including unions and health systems, taken together represent tremendous power and influence.

It is possible to imagine a new era of experimentation with collective bargaining, especially since the issues that are causing these organizations to support collective action have common root causes across geographies and health systems.

To have impact, such experiments in community-based organizing and social dialogue need not be on a giant scale. Success will breed interest and learning.

What could be better?

John August is the Scheinman Institute’s Director of Healthcare and Partner Programs. His expertise in healthcare and labor relations spans 40 years. John previously served as the Executive Director of the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions from April 2006 until July 2013. With revenues of 88 billion dollars and over 300,000 employees, Kaiser is one of the largest healthcare plans in the US. While serving as Executive Director of the Coalition, John was the co-chair of the Labor-Management Partnership at Kaiser Permanente, the largest, most complex, and most successful labor-management partnership in U.S. history. He also led the Coalition as chief negotiator in three successful rounds of National Bargaining in 2008, 2010, and 2012 on behalf of 100,000 members of the Coalition.