Healthcare Insights: Labor-Management Partnership in a Time of Crisis

By John August

Recently, Pam Brier, an accomplished healthcare executive in New York City published an article in the Harvard Business Review, "How Labor Management Partnerships Can Deliver Outsized Results”.

The article recounted her many years of collaborative work with the unions at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, NY that began in 1997, nearly 30 years ago. Cornell-ILR faculty were participants in the design and facilitation of the partnership.

“Wages, benefits, and financial stability will always create tension, “ states Grier. She adds:

I argue that the current public policy, workforce shortages, technological advances, including A.I. and industry consolidation tensions which threaten the stability and sustainability of great patient care and great jobs in healthcare today has created an environment as challenging today as before healthcare workers started large scale union organizing in the late 1960s. For more than 40 years, ongoing efforts to reduce healthcare spending while improving access to and the quality of care has led to increasing pressures on labor and management to perform.

That pressure is building more conflict and less resolution of root causes of the problems we face in healthcare, which have remained the same over this long period.”

At the heart of Brier’s argument for labor-management partnership is the essential role that the individual worker contributes to improvement and problem-solving: “Remember that leadership is not the sole provenance of managers. People who work as clerks or serve meals or mop floors may also be leaders in their own communities, churches, and schools. Identify these potential leaders for your partnership and cultivate them. They are opinion-shapers and often well-regarded by peers.”

From my own experience in leadership of the Kaiser Permanente Labor-Management Partnership (LMP), it is clear that partnership relies entirely on the experience of the frontline worker, manager, and physician for success.

For much of this year, there has been a theme to many of the articles I have written: that public policy changes such as projected cuts to Medicaid, anti-vaccination opinion coming directly from the highest levels of the federal government, cuts and even elimination of life-saving research, and anti-immigrant surveillance and detention, all have caused harm to patients and communities. I have also discussed how these and other policies place the healthcare provider in conflict with their oath “to do no harm” in the practice of seeing patients. Such conflict adds to the already high levels of burnout and moral injury that have existed in the healthcare workforce.

Funding cuts, external pressures on the ability of healthcare workers to be able to administer and carry out needed healthcare services, and the often-unspoken concern of how executive leadership of healthcare institutions will cope with these changes and what impact the changes will have on patients and providers, all leads to deep concern and potential conflict in the workplace.

We also know that the impact of the pandemic, inflation, and the largest workforce shortages in the history of the healthcare industry led to more conflict in health care in the last three years than in the twenty years before.

We must now add these more recent additional external forces to the already existing crisis and as a result… Additional conflict appears inevitable.

We know from experience, as conflict increases, root causes of conflict tend to be overshadowed and remain unresolved, making for a trajectory of increased causes of conflict.

In this moment of growing conflict in healthcare, I am reminded of the outstanding and prescient language in Tom Schneider and John Stepp’s article, The Evolution of U.S. Labor-Management Relations, written in 1998:

“The great upheavals in the early 1980’s generated little gain. Labor and management generally behaved as though no real change was needed in the institutions, policies, and practices that had been developed over the previous decades. They seemed to believe that it was necessary only to make cuts and tweaks to the system and then continue to act as they always had.”

But they were wrong. The old systems of organizing work and work relationships were no longer productive. U.S. companies remained unable to produce quality products at competitive prices in global markets. Further, economic, political, and technological changes were rendering many aspects of the traditional industrial relations model obsolete. The master contract had vanished, the strike weapon had been blunted, and many unions had been added to the “endangered species” list. By the late 1980s, widespread concern about U.S. competitiveness and its link to Americans’ declining standard of living led to a search for ways to attain higher levels of performance.” (emphasis added)

While Schneider and Stepp were writing about the demise of American manufacturing and the diminishing role of unions in those sectors, their observations about that period ring true for healthcare today. The authors cited major industrial conflicts in the 1970s and 1980s. We remember that period of major strikes, plant closures, the growth of anti-union campaigns, the loss of millions of good paying jobs, and the loss of millions of union members. While it is clear that the “cuts and tweaks” in the system did not work, it is more accurate to conclude that there was little innovation or new ways of thinking about labor-management relations on a large scale that might have prevented the losses to companies, workers, and ultimately the nation as a whole.

In similar fashion, we must remind ourselves that fundamental transformations in healthcare financing and delivery date back to that same period of the 1980s. “Sensitivity in the early 1980s by public and private payers to dramatically rising health care costs resulted in increased pressure on traditional providers to contain costs and on consumers to share more of the costs (Juffer, 1982; Business Week, 1983). (emphasis added). Rising costs caused increased interest in HMOs for their cost containment potential (owing, for the most part, to their lower rates of hospitalization), even among employers who had previously avoided HMO involvement."

The article cited here refers to but one of the many transformational restructurings in healthcare that emerged in the early 1980s, in this case the beginnings of the health maintenance organization (HMO), which had a very limited role in the traditional financing model of fee for service up to that time. It is critical to note that the underlying rationale for this new competitive model to traditional healthcare was “the dramatically rising healthcare costs.” Indeed, the HMO model impacted all delivery systems as more and more patients enrolled in HMOs as their employers sought less expensive health care for their employees.

In this excerpt from the history of the labor management partnership at Kaiser Permanente, it is clear that the emergence of HMOs had a tremendous impact on the efficacy of the Kaiser business model, and on labor relations.

“In the early 1990s, labor relations between Kaiser Permanente (KP) and its workforce hit rock bottom. Faced with mounting competition from for-profit HMOs, KP responded by placing the burden squarely on the shoulders of its workers by cutting jobs, wages, and benefits. Strikes erupted throughout California and Oregon, threatening to derail KP as an organization and disrupt the livelihood of union members.

The situation was dire, and something had to change. This prompted a turning point, as workers realized they needed a new strategy to protect their future — not more sacrifices”

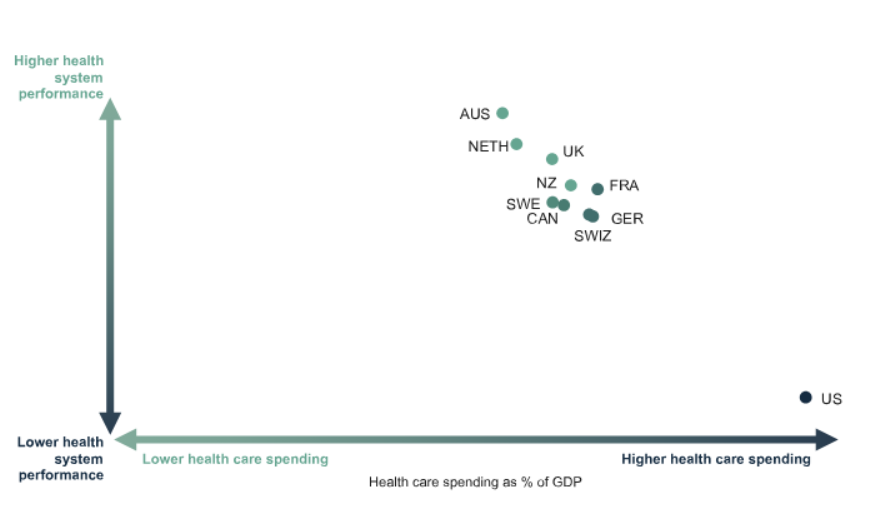

Over the past 40 years the healthcare industry has grown to nearly 20% of GDP, more than $4.5 trillion in annual spending. Nonetheless, the health of the American population continues to be last among all other industrial nations, and in many measures comparable to much poorer countries.

This chart illustrates that the richest country in the world has the highest spending with substantially sub-optimal performance in health outcomes.

Sadly, these trends continue unabated.

The similarity of the demise of manufacturing in the U.S. in the 1970s and 1980s to the spending-performance crisis in U.S. healthcare is stark. In both cases, the American people broadly and the people who work in these industries suffer the disruption and disappointment of failed systems.

And we are in a time of great conflict.

Why would labor-management partnership be relevant in such a time? To many, partnership seems naïve or even wrong-headed.

Quite to the contrary, it ought to be a time to consider what we have learned from previous declines in industry and the devastating impact such decline has had on the social fabric as a whole. There were many efforts in the manufacturing sector to engage in partnerships between labor and management and among some of the largest corporations including IBM, Kodak, General Motors, Hunt Wesson, and major steel corporations, among others. There is much to learn from what they attempted and succeeded in doing. Indeed, the most successful labor management partnerships in healthcare based their efforts on some of the principles and methods learned in the 1980s and 1990s in manufacturing.

It is generally acknowledged that the partnerships in the manufacturing sector came too late and were not widespread enough to make a difference, even though each of them showed promise.

Before I discuss the building blocks of successful Labor-Management Partnerships (LMP) it is important to understand and appreciate that an LMP cannot on its own change public policy or the externalities which create pressures and conflicts in the impacted systems and enterprises. Some argue forcefully that LMPs mask the real issues that cause conflict and poor performance and it is better to encourage conflict until changes in public policy eliminate the root causes of poor performance. That is a strong argument we hear among those who believe that Labor-Management Partnerships ought to have no place in this time of great conflict and inequality.

I think that is a narrow view.

Labor-Management Partnership as defined in the case of Maimonides Medical Center in Pam Brier’s article, or in the case of Kaiser Permanente or past collaborative efforts in manufacturing were all based on the principle of achieving measurable and sustained improved performance through reliance on the empowerment and mobilization of frontline workers:

At Maimonides there was demonstrable success:

- a 50% reduction in hospital-acquired infections;

- a 50% reduction in patient falls; major improvements in response time to cardiac monitors (down to less than one minute);

- 75% increase in unpaid bill collection;

- a 93% rate of patient meals delivered on time;

- a 63% reduction in union grievances; and the introduction of innovative new operating room procedures that prevented errors.

All of these improvements occurred due to the investments made in the organization of new work systems and work relationships. People were never asked to work harder or faster. Rather, training and facilitation brought the diverse skill sets and experience of frontline workers together to learn to solve problems through their knowledge gleaned from direct day-to-day experience and the application of scientific methods of improvement.

At Kaiser Permanente, more than 3500 unit-based teams go to work each day in laboratories, operating rooms, call centers, hospital wards, procurement and warehouse settings, pediatric clinics, and business offices to identify gaps in performance and create new systems that improve performance. “As of August 1, 2022, based on unit-based team self-reporting of organizational savings, $602,656,955 in savings has been achieved.” (“The Promise of the Kaiser Permanente Labor-Management Partnership” chapter in forthcoming book, Collective Voice in the 21st Century, Cornell ILR Press).

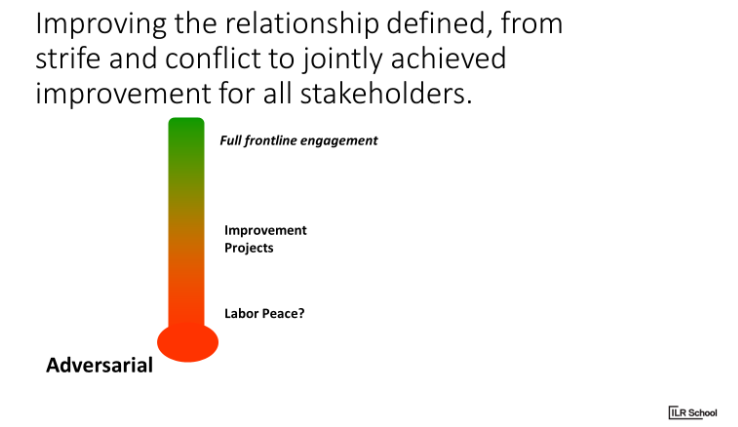

LMP’s develop on a continuum between committed leaders in labor and management, as illustrated below:

Here are the building blocks of partnership:

- Moving to “labor peace”:

- Provide Skilled facilitation. We will provide experienced facilitators who will assist the parties in the establishment of the first step: to create a foundation of mutual interest to improve the relationship

- Assist the parties to identify the problem(s) to be solved that create conflict

- Assist the parties to identify the root causes of the problem(s) that create conflict

- Provide training and execution of the conflict resolution process known as Interest Based Problem Solving (IBPS)

- Assist the parties in the selection of a pilot problem-solving topic which the parties agree would be helpful to the relationship if solved

- Assist the parties in monitoring success and establishing a joint labor-management team to periodically but regularly assess progress and sustainability of problem-solving. Assist in how to adjust and review

- Entertain new approaches to conflict resolution other than traditional grievance/arbitration, such as non-punitive “Issue resolution/corrective action”

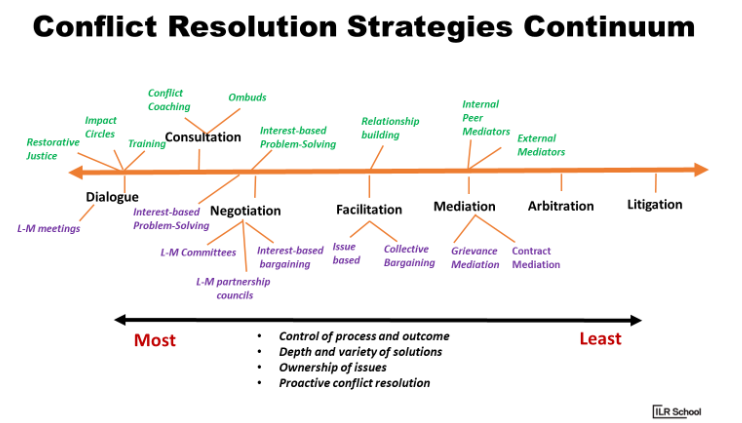

- Introduce conflict resolution continuum:

Please note that the more innovative strategies of conflict resolution on the left side of the graphic are associated with the most effective outcomes. This recognition is often a surprise to practitioners.

2. Moving to Improvement Projects

- Assist the parties in the establishment of a dialogue about performance improvement as the central purpose of the improvement of labor relations

- Assist the parties in the dialogue to see that performance improvement is a joint endeavor and responsibility; that performance improvement is not about speed-up, or a matter made up of other negative connotations often associated with the term “performance improvement. Rather, the outcome of the dialogue is to achieve a consensus between the parties that the process of performance improvement is to achieve the highest quality of product, the highest quality of customer satisfaction, the best possible price point in the marketplace, and keeping in mind that none of these goals are possible unless an equal goal is to achieve and maintain the best place to work in the market with the full engagement of the employees

- Assist the parties in the identification of a performance improvement project as a first pilot experiment

- Such projects could be in a small sub-departmental unit; a whole department or service line, or facility-wide

- However, to enable success, such a project(s) should have certain attributes:

- It is achievable (realistic and not aspirational)

- If successful, perceived as such by both parties

- Affordable: don’t start a project that will require substantial financial investment… then

- Monitor implementation; share results with stakeholders

- Learn what worked and why

3. Moving to full frontline engagement (system-wide performance improvement; labor-management partnership)

- Establish shared purpose

- Establish joint governance structures at executive, facility, departmental, unit levels to maintain continuity, strategy, accountabilities

- Traditional collective bargaining moves to Interest Based Bargaining

- All conflict resolution through IBPS

- Move from Grievance/Arbitration to issue resolution/corrective action

- All departments/units trained in performance improvement processes

- All departments develop improvement projects which align to agreed-upon strategic goals of the enterprise and the union

- Develop joint systems of reward and recognition

- Monitor employee engagement

- Some enterprise -wide goals to consider as part of the full engagement of the frontline:

- Workforce Planning and Development

- Career security: requires some flexibility in traditional rules such as bumping rights and strict seniority in exchange for life-time employment with training for new and expanding positions and guaranteeing pay and seniority throughout transition

- Improve health of the workforce: health and productivity, lower cost of the health plans

Collective voice empowered towards a shared vision of change and improvement is the powerful foundation of Labor-Management Partnership.

Consider this: that for the population of working age, the bulk of each day involves work. That work each day builds knowledge and experience about the work and work processes; yet for most, that knowledge and experience is applied in daily routine without it being channeled toward a truly shared purpose. What if it was?

LMPs have shown that great progress can be made in spite of negative external forces. While we may be living in more extreme times than any of us have experienced before, we should not count out the impact of collective action for improvement in the workplace.

We may have forgotten that General Motors, once the largest corporation in the world and virtually 100% unionized, declared bankruptcy in 2008. In 2010, I wrote:

“Professor Harley Shaiken of UCBerkeley told the New York Times that What’s come out of the crisis (bankruptcy) is a realization that the interests of both sides are aligned.

As healthcare leaders, we know that another great American tragedy is preventable, and not inevitable: hypertension, “the silent killer.” But in order to prevent hypertension, first you have to know that you have it. Then you have to make major corrections in behavior and outlook to cure it. Like the hypertension patient who is unaware that he or she has the disease, we have got to get the facts, realize their impact, and transform. In fact, we are at the center of trying to create a system to help hypertension patients get the facts and transform. We also need a system to align our interests and act on the economy before it is too late.

In our Labor Management Partnership Agreement of 1997, unions, management, and physicians agreed to align our interests in the face of the rapidly changing external forces all around us.

That was more than 13 years ago and we have made great progress. Now more than ever, we must respect the struggles that came before us, both our own, and those of our sisters and brothers in the U.S. auto industry. We have choices to make in the interest of the very future of our society.”

Today is an important time to reflect on the theory and practice of labor-management partnership.

John August is the Scheinman Institute’s Director of Healthcare and Partner Programs. His expertise in healthcare and labor relations spans 40 years. John previously served as the Executive Director of the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions from April 2006 until July 2013. With revenues of 88 billion dollars and over 300,000 employees, Kaiser is one of the largest healthcare plans in the US. While serving as Executive Director of the Coalition, John was the co-chair of the Labor-Management Partnership at Kaiser Permanente, the largest, most complex, and most successful labor-management partnership in U.S. history. He also led the Coalition as chief negotiator in three successful rounds of National Bargaining in 2008, 2010, and 2012 on behalf of 100,000 members of the Coalition.