Changing Mindsets

Full-time jobs and their perks are giving way to an emerging gig economy that touts greater freedom and choice, but hurdles confront workers and employers looking to adapt, according to the speaker at Thursday’s Future of Work series event.

A gig economy or “independent work” has become the norm for 27 percent of working age people in the U.S., or up to 68 million, and for 28 percent of their counterparts in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Spain and Sweden, or up to 62 million, a recent McKinsey Global Institute survey found.

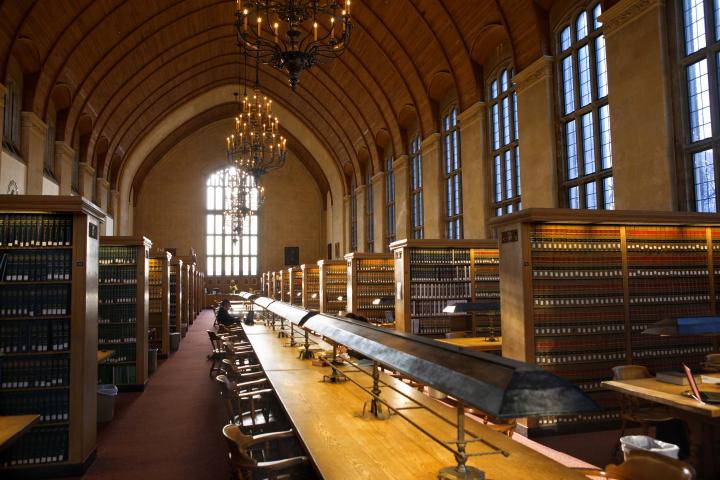

Susan Lund, economist and partner at management consultant, McKinsey & Co., shared survey results at the forum, sponsored by ILR School’s Institute for Workplace Studies, in Conference Center in New York City

While many independent workers have embraced the gig lifestyle as an alternative to the traditional 9-to-5 job, others have done so reluctantly because they are unable to find full-time work or are not making enough, even with full-time employment.

“So, who are these people and what are they doing?” asked Lund.

A McKinsey analysis found that 94 percent of all net new jobs over the last decade were freelance, temp, part-time or gig labor. The common trait for these worker categories is that all earn money outside the traditional, full-time scheme under a single employer, Lund said.

The majority of independent workers are engaged in labor service occupations, including massage therapy, personal training and accounting. The newest class of these workers are earning income by exploiting digital platforms, such as car driving service, Uber.

Another group of workers are tapping online sites, such as eBay, to sell goods. The smallest group is making money by leveraging their assets through providers like Airbnb where they can rent out their apartments. McKinsey also found enthusiasm for independent work was very similar for men and women as well as for workers spanning different generations.

The event’s moderator, Louis Hyman, associate professor at the ILR School and director of the Institute for Workplace Studies, said digital platforms have wider implications beyond just offering consumers an array of choices.

“Companies like Uber after all are not about the convenience of the app or even the engineering behind the app, but what it means for our society, our economy and, of course, for our work lives,” Hyman said.

More than half of independent workers picked this route to supplement their income and may still have a traditional full-time job, such as a teacher who tutors on the side. One finding that bodes well for the independent work trend is that it has little to do with concerns over a bad labor market.

Up to “72 percent of independent workers in the U.S. say this is their preferred way of working,” Lund noted. In addition to flexible hours and being able to choose where you can work, independent workers said they found this path offered more creativity and opportunities for career advancement, she added.

A sizable number, 28 percent, of workers say they want a traditional job, but can’t find one, Lund said. This is not something that should be overlooked or ignored, she noted, but maintains that “as economies improve, we would not expect [the independent work trend] to go away and shrink.”

The emergence of independent work also has implications for companies that need to start thinking about how they can design their workplace “to mimic what people are getting out of independent work,” Lund said. Companies are surprised to hear with more frequency that employees are turning down promotions that require them move to a different city.

Most companies’ human resources departments are “still in the mindset of ‘we are trying to find a candidate who is going to stay with us for 10 years,’” Lund said. This is antiquated thinking that needs to evolve if companies hope to successfully recruit and retain talent, she added.

“The whole relationship between employer and employee in many ways has been shifting to more of an arm’s length transactional-type mode,” she said.

Meanwhile, as competition in the independent work space grows, participants need to hone in on what they can offer to “differentiate [their] skills that enable [them] to command a premium and so [that they] get a steady stream of work,” Lund said.

Historically, self-employment had been the norm for the U.S. and in Europe dating back to the 1900s. But the Industrial Revolution and the rise of factories and the manufacturing assembly line gave birth to a payroll employment system where employees clocked in weekly for at least 40 hours.

And just as the Industrial Revolution had done, the digital era is driving a new working structure.

“On the one hand, you have a lot of automation substituting for manufacturing labor,” Lund said. And then “you have digital platforms like Uber and Upwork that enable people to find work independently.”

Another surprise finding for McKinsey was that independent workers who chose this path felt their income was more secure than employees in traditional jobs.

“Once you crack the nut on being your own boss, being an independent worker, you know you are not going to be fired,” Lund said.