Discovering Frances Perkins

Kirstin Downey first heard the name 'Frances Perkins' while on a trolley tour of Washington, D.C., in 1988.

As the group passed a U.S. Labor Department building named in honor of one of America's most influential women, the tour guide asked, "What American woman had the worst childbirth experience? Frances Perkins. She spent 12 years in labor."

Downey, who will discuss her new biography of Perkins on March 12 at ILR, said in an interview, "There are hardly any buildings in Washington named for women, (and) the only memory of Frances Perkins was a joke? It made me wonder, who was she, really?"

Perkins, named secretary of labor by Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, served 12 years in the post. She was the architect, Downey said, of some of the most important social welfare and legislation in the nation’s history, including Social Security, unemployment compensation, child labor laws and the 40-hour work week.

"Almost everything we rely on today to get us through this recession were her programs," said Downey, who spent 21 years at The Washington Post, where she covered economics, the workplace and other issues, including the beginnings of the current mortgage meltdown.

In the late 1990s, Downey was driven to begin a biography of Perkins after receiving an inquiry from a worker who had been locked in his office. What were his rights, he asked Downey.

In researching the answer, Downey came across Perkins's critical role in improving workplace safety after the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Perkins helped lead the push for reform of New York state's labor code. The new legislation became a model for the rest of the country.

Perkins, a social worker in New York at the time of the Triangle fire, saw workers jump to their deaths from the burning factory.

"She witnessed this horrible spectacle, then played a key role in fire safety. It was really remarkable," said Downey, whose lecture March 12 is sponsored by the Kheel Center for Labor Management Documentation & Archives.

The book, which will be published March 3 by Random House, is entitled "The Life of Frances Perkins: FDR's Secretary of Labor and his Moral Conscience."

"I couldn't believe this woman did so much and nobody knows," Downey said. "How did this happen?"

Further research, including more than a week at the Kheel Center , revealed answers.

Perkins was results oriented and didn’t linger for glory when a project succeeded, Downey said. "She would move on and be getting something else done."

Perkins's distaste for the press didn’t help her profile, either, Downey said.

"She didn't really like reporters. She wasn't as cooperative with them as she could have been. She felt they were intrusive and refused to cooperate in a couple of stories that were key" to forming reporters' views of who constituted Roosevelt's brain trust.

Perkins was leery of reporters for personal reasons, too.

"Her husband was mentally ill, he had bipolar disorder. Perkins was worried about the press finding out and putting him in an embarrassing situation," Downey said.

Sexism also played a role in Perkins's low profile, the author said.

"There had never been women in positions of power … a lot of men were reluctant to give credit for achievement to women," she said. Some of Perkins's White House colleagues were irritated by her, Downey said, because she "talked too much."

Roosevelt, however, listened to Perkins, Downey said. So did President Harry Truman, to whom Perkins served as an adviser, and New York State Governor Al Smith.

Perkins, the daughter of middle-class shopkeepers in Worcester, Mass., engineered a remake of her own image by the time she was in her late 20s, Downey said.

She dropped her birth name – Fannie – and became Frances, lopped two years off her age and switched from the Congregational Church to the Episcopal Church.

In her 30s, Perkins purposefully appeared matronly in order to gain the trust of men, Downey said. Men would be more trusting of her as a peer if she looked like their mothers, she thought.

Emotional intelligence helped Perkins navigate Washington, Downey said.

"To some extent, she expected the reality of it (sexism). She was wise about the human condition," Downey said.

"She knew she lived in a man's world, so she came up with ways to deal with men and their wives," Downey said.

After formal dinners, Perkins didn't retreat with the men to smoke cigars and discuss politics, Downey said. She stayed with the wives.

"It was really hard, she was under terrible pressure and way she dealt with it by praying a lot, going to church a lot, going on religious retreats," Downey said.

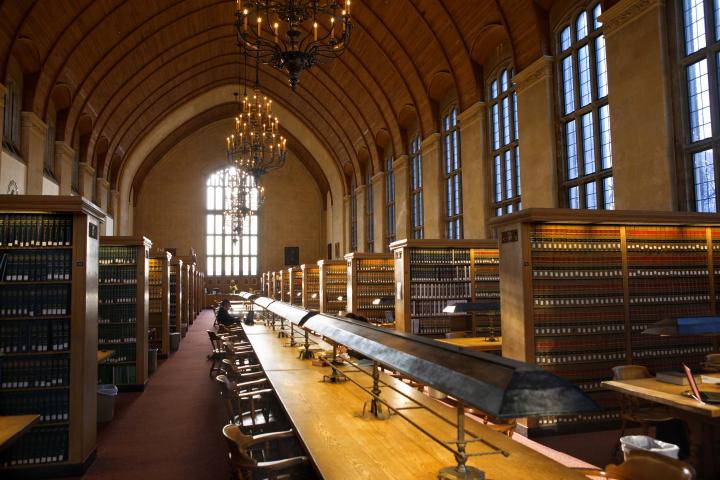

Perkins held appointments as an ILR visiting lecturer from 1957 to 1965. She would lecture for a few weeks at a time, depending on her availability. Recordings and transcripts of her lectures are available at the Kheel Center.

During some of her appointments, Perkins lived at Telluride House on West Avenue in Ithaca. "It was probably the happiest phase of her life," Downey said.

Perkins loved the intellectual discourse and fraternity house atmosphere she shared with her student housemates – all men, as she was the first woman Telluride resident, Downey said.

One of Perkins's housemates was Paul Wolfowitz, who became president of the World Bank. Another was Allan Bloom, then a faculty mentor at Telluride house. Bloom wrote "The Closing of the American Mind."

"She had a lot to share with the younger generation. She enjoyed intelligent young people," Downey said.

"She also needed the money," Downey said. "She had been a civil servant all her life, had no health insurance. At the end of her life, she needed a job."

The lecture about Perkins begins at 4:30 p.m. March 12 in 105 Ives Hall. The lecture will be followed by a book signing event. Both are free and open to the public.

More information about Perkins is available at http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/texts/lectures/perkins.html and at http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/library/research/questionofthemonth/jan03.html.