Foreign Service Careers

The U.S. Department of State Foreign Service, with more than 260 posts across the world, needs the skills an ILR education provides, Senior Foreign Service Officer Robert Dry told students Thursday.

Policy, international affairs, labor-management relations, human resources and other areas studied by ILR students are a fit for a breadth of foreign service career paths, Dry said.

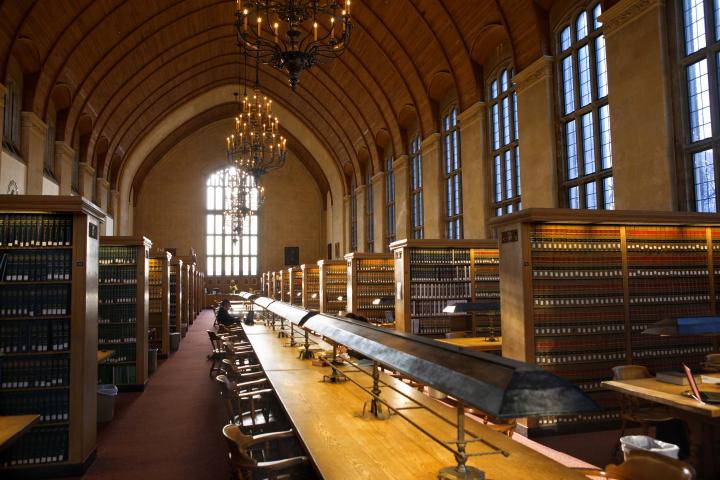

He met with 14 ILR graduate and undergraduate students as part of a day-long recruiting effort at Cornell. Donna Ramil, associate director of ILR International Programs, organized the meeting, held in the ILR Conference Center.

Dry, a 36-year veteran of the U.S. Foreign Service who spent much of his career in Arabian Gulf countries, is a diplomat in residence at City College of New York.

He is among 14 officers serving one-year assignments as diplomats in residence on college campuses around the country.

Their roles include recruiting candidates for full-time jobs and internships with the state department, the nation’s lead foreign affairs agency.

Marijke Schouten '10 and Paulisa Brown '10 have worked as U.S. Department of State interns in human resources-related roles.

Much of the work of Neresa Di Biasi '11 will do this summer as in intern in the state department's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor will be on policy and international affairs. Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and current Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have asked the bureau to focus on women's rights as a human rights issue.

Dry served as charge d'affaires or acting ambassador and deputy chief of mission at the American embassy in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman.

He was responsible for obtaining unfettered access to Omani military facilities for United States' armed forces as the Afghanistan war was staged.

During that time, he said, a typical 12-hour workday of a foreign service officer stretched to 18 hours and officers were on call 24 hours a day.

"This was a very interesting labor relations situation," Dry said.

Embassies are usually staffed by a mixture of federal; civil servants, foreign service officers and foreign nationals. At one of his posts, 100 different languages were spoken by staff members, Dry said.

Foreign service officers – who are unionized -- are often rotated into a new location every two years, he said.

"Issues can arise," Dry said, and sometimes it is a disagreement by employees with Department of State policy.

The "constructive dissent channel, he said, "is different than whistle blowing, for officers who see a policy that is not appropriate for the United States."

Employees can decide, Dry said, either "I can live with it (policy) until I rotate. Or, I can write back to Washington on how this policy is being implemented. You have the option of the constructive dissent channel."

Another mechanism serving employees' needs, he said, is a "built-in sense of flexibility."

Officers can bid on other openings before their assignment is completed and leave their post for a new one "and there will be no negative," he said.

"There is a vast amount of complexity with foreign policy," Dry said. "We have an obligation that, in a sense, is higher than any ideology or political ambition."

Before considering a foreign service career, he said, ask "how strong is that sense of your own personal moral compass?"

"Out in the field, that is one of the few things you can really rely on," Dry said.