Managing Human Capital in Global Supply Chains

The challenges of developing rigorous, yet flexible human capital practices for workers in the global supply chain were discussed by international policy leaders, Fortune 500 executives and ILR professors March 7.

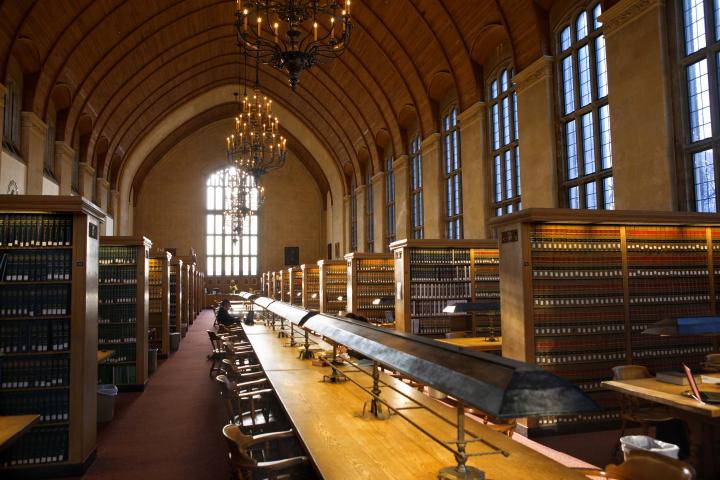

Organized by the International Labour Organization, ILR and the Worker Institute at Cornell, "Managing Human Capital in Global Supply Chains: Lessons and Applications from Today's Leaders" was held at the ILR Conference Center in New York City.

Despite conflicting labor policies, cultural differences and lack of local and national government transparency, some participants stressed that progress is being made to improve practices for workers thousands of miles away.

One of the most effective approaches, they said, is organization-wide integration of a social ethic that upholds workplace standards such as the International Labour Organization Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

The declaration calls for freedom of association and collective bargaining, elimination of forced labor, abolition of child labor and elimination of workplace discrimination.

Social responsibility is good for business, some said, but convincing other corporations of that can be difficult. Harry Katz, ILR's Kenneth F. Kahn Dean and Jack Sheinkman Professor, urged attendees to initiate research that would show the value of social responsibility for corporate business models. "Otherwise, naysayers won't accept its viability," he said. "Proof of an improved bottom line," he said, "is needed to get the momentum going."

Nancy Donaldson, director of the International Labour Organization office in Washington, D.C., said supply chain profitability and corporate social responsibility can complement one another.

Buy-in of top leadership is critical for improving labor standards in the world’s supply chain, Donaldson said, and making headway remains difficult. "How do you measure human rights? How do we get better traction with governments and the investment community?"

Despite challenges around responsibility, she said, "I do think we’re making progress."

Amy Luinstra, director of policy and research for Better Work, a program of the International Labour Organization and the International Finance Corporation, said: "From sweatshop to sweet spot is very difficult. It's possible … (but) getting there is tough."

Compliance with International Labour Organization standards can be linked to higher productivity, Luinstra said. "Factories where workers perceive better working conditions are more profitable." Also, win-win propositions for workers and corporations can be inexpensive, she said.

Adam Greene, vice president of labor affairs and corporate responsibility for the United States Council for International Business, said: "Some companies do a good job with labor practices, but a 'massive gap' between laws and compliance exists in many nations." It is particularly difficult to implement human capital practices in the unregulated, informal economies of some developing nations.

Attendees agreed that social responsibility for the supply chain requires cooperation among industries, private and public sectors, corporations and governments.

Jean Baderschneider Ph.D. '78, recently retired vice president of global procurement for ExxonMobil, urged attendees to push for social responsibility in their corporations for both ethical and business reasons. "There are huge liabilities lurking out there. One way to avoid them is to get on this train."

Appealing to a corporation's profit motive in order to drive social responsibility is valid, she said, and proponents have to be relentless. "You can't sacrifice principles, ever."

One corporate executive said educating employees on corporate social responsibility is "important and necessary," particularly for those who oversee vendors and licensees.

Steve Miranda, managing director of the ILR's Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies (CAHRS), said, "There's been a shift by corporations from thinking about corporate social responsibility as 'what we do with our money' to 'how we make our money.'" He also shared that well-communicated corporate social responsibility programs serve as terrific "brand enhancements" when implemented.

ILR Professor Sarosh Kuruvilla, whose research informs government policy and practice in China, India and other countries, discussed the difficulties of obtaining quality social responsibility audits.

Some corporate representatives said they use factory visits, community dialogues and employee hotlines to supplement audit information because "checkbox" auditing of workplace practices is not enough.

Lance Compa, an ILR faculty member who researches and writes about international labor rights, provided an overview of trade laws and regulations that govern public and private sector supply chains.

Amber Thomas MILR '14, said collaboration among industry sectors, governments, non-governmental organizations and others is key to increasing corporate responsibility.

"Hearing the genuine care you have for this and your openness to communication and willingness to share challenges – I'm really encouraged," she said.

Ingrid Jensen MBA/MILR '13 said the discussion gave her "great hope."

More companies are seeing the business value of integrating social responsibility into supply chain transactions, said Karen Tramontano, chief executive officer of Blue Star Strategies, which advises corporate clients and others.

"You see the changes. They're undeniable," she said.