Seeking Culture Change

As they attempt to gain flexibility and save money, more businesses are incorrectly classifying workers as "off the books" independent contractors and creating expensive social and legal problems for government, workers and themselves.

Although employers are being held accountable more often, misclassification enforcement is challenged by rapidly growing numbers of impacted workers -- perhaps one in 10.

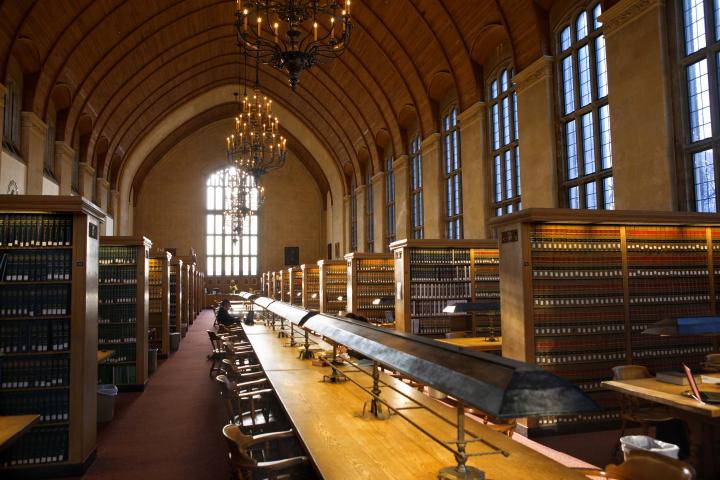

In framing that discussion Thursday in the ILR Conference Center in New York City, ILR Labor and Employment Law Program Director Esta R. Bigler '70 said that the issue encompasses workers in a breadth of professions and industries. A recent case of misclassification involves exotic dancers.

Ms. Bigler summarized misclassification issues as "complicated."

The four speakers and audience of attorneys, arbitrators and human resources professionals seemed to agree during "Employee Misclassification: An Enforcement Update."

Solicitor of Labor M. Patricia Smith of the U.S. Department of Labor said there is a groundswell of interest among states -- particularly in the Northeast and Midwest -- in identifying and regulating misclassification.

Lost revenues to Social Security, the Internal Revenue Service and other agencies help motivate government entities to work together, she said.

The United States government has lagged behind the states in enforcing misclassification, but $25 million is devoted to it in President Barack Obama's proposed federal budget, said Smith, a former New York state labor commissioner.

Expect to see more information sharing between federal agencies such as the Internal Revenue Service and the Department of Labor, Smith said, adding, and "I would not be surprised to see misclassification legislation passed in this Congress."

Laurie Berke-Weiss '71, a partner at Berke-Weiss & Pechman LLP, event co-sponsor, called employee misclassification "a minefield that’s become much more dangerous."

"The mere fact that you have an agreement" between a worker and an employer does not protect either one, she said.

Most cases are decided by minute details around issues such as who controls the worker, the permanence of the work relationship and whether the work is integral to the employer's business, Berke-Weiss said.

Conflicts in misclassification case law also blur the line between risks and rewards for employers considering a contract with an independent worker, she said. "It's not always an easy call."

"The Cost of Misclassification in New York State" (http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=reports ), published by ILR in 2007, details the billions lost through uncollected Social Security, unemployment and income taxes. Many consider the report a foundation document for reformation of misclassification.

Workers and taxpayers typically absorb the costs of misclassification, which occurs when an employer relies on an independent worker as a regular employee, but treats him as a contractor by not providing benefits such as overtime, worker's compensation and health insurance.

Although misclassification occurs most egregiously in the underground economy, it is also a problem in some legitimate business, speakers said.

Pamela Tolbert, ILR's Lois S. Gray Professor of Industrial Relations and the Social Sciences, said research she and colleagues conducted show that independent contractors can impact job attitudes of regular workers in a negative way.

Employers, she said, "must think very carefully about these unintended consequences."

Although use of independent contractors might not be intended as a disciplinary measure, regular workers often perceive it that way and fear their jobs are in jeopardy, Tolbert said.

Less skilled workers feel more threatened by temporary workers than do highly skilled workers, and feel less loyalty to employers, she said. The drop in loyalty may result in increased absenteeism and lower productivity, which can have economic and policy ramifications.

About one in 10 workers in today's work force is temporary -- an increase of about 1,000 percent in the past four decades, Tolbert said.

Jennifer S. Brand, executive director of the New York State Joint Enforcement Task Force on Employee Misclassification, said that the task force -- working with state and local agencies -- has identified nearly $500 million in unreported wages since 2008.

Crossing the spectrum of worker skills and industries, misclassification is particularly apparent in the construction industry, she said.

The New York State Construction Industry Fair Play Act, enacting new classification standards and penalties for employers who do not follow them, went into effect in October.

"Our biggest challenge is to make sure the change we've seen continues," she said, noting that 19 other states have started similar task forces.

Misclassification can be both blatant and subtle, Brand said, and is sometimes identified by door-to-door business district "sweeps" conducted by the task force.

Employers, she said, "are taking notice ... I think we're seeing a change."

More information about misclassification information presented at the event can be seen at http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/law/events/Employee-Misclassification-Enforcement-Update.html.