Theme of Hope

Employers say that it's difficult to accurately assess the risk of hiring someone with a criminal record.

For people looking to start a new life after incarceration, this is one of many barriers that makes it hard to find work.

What can be done to increase the hiring of qualified people who have criminal records?

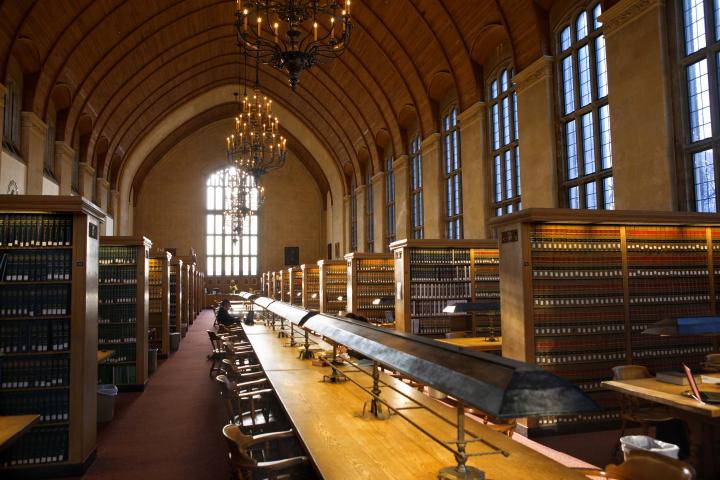

This was the focus of the Richard Netter Conference on Criminal Records and Employment, sponsored by the Cornell ILR Labor and Employment Law Program, in conjunction with the Cornell Law School. The conference was held Dec. 9 at ILR's New York City Conference Center.

Esta Bigler '70, director of the ILR Labor and Employment Law Program, said, "It might be the first time that a program on this topic brought together in one room all of the interests and voices on the issue -- lawyers, social scientists, representatives of background screening agencies, government officials and company executives -- for a real exchange of ideas."

P. David Lopez, general counsel for the Equal Employment and Opportunity Commission and a conference presenter, said that the issue is not just about employment, but about society.

"This has personally affected my family, so I know the emotional struggles this creates. We need to keep focused on the human face of this issue."

Barry Hartstein '73, shareholder, Littler Mendelson P.C., during his presentation said, "We're talking about a societal problem more than an EEO issue."

In his conversations with employers, Hartstein said he hears them saying that it makes sense to give consideration to applicants with criminal records, but there are legal and other implications.

"There are so many factors to weigh in the balance," he said, citing Occupational Safety and Health Administration obligations and negligence issues. "The challenge is that employers are not just looking at this through an EEO lens, but through many lenses."

Conference panelist Adam Klein '87, partner, Outten & Golden LLP, said a major concern for employers is how to effectively analyze the risk associated with hiring someone who has a criminal record.

"There are no systematic measures, in most cases, for employers to evaluate criminal records. Information can be so inaccurate, and the process can be subjective," he said.

Klein said what's been missing in the discussion is the role of industrial and organizational psychologists and the need for science-based selection tools for employers.

John Hausknecht, an associate professor in ILR's Human Resource Studies Department, and an industrial and organizational psychologist, told conference attendees that little research has been done on criminal records and employment. But, there is a growing academic interest in the topic.

"A key question is, do criminal records predict job performance? We can't show much evidence of this yet, and it can be very costly to try to assess someone's trustworthiness," Hausknecht said.

Several of the panelists stressed that there is a disproportionate number of African-American and Hispanic men with criminal backgrounds who cannot find employment.

Lopez said this also raises the question of discrimination based on race in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act when employers automatically exclude people with a criminal record.

In his opening remarks, lawyer Cornell William Brooks said joblessness for black men stands at 40 percent, and that one-third or more of those who have been incarcerated experience no earnings or income growth over a decade.

"This is a civil rights challenge for them and an economic development challenge for us," said Brooks, president and chief executive officer, The New Jersey Institute for Social Justice.

"It's unacceptable, and a national tragedy," Klein added.

While there are still many problems to overcome, Brooks emphasized that events like the Netter Conference are a big step toward finding solutions.

"The theme of this conference is hope. I can't help but believe that academics, social scientists and others coming together can make a difference in addressing this issue."