"A Transformative Experience"

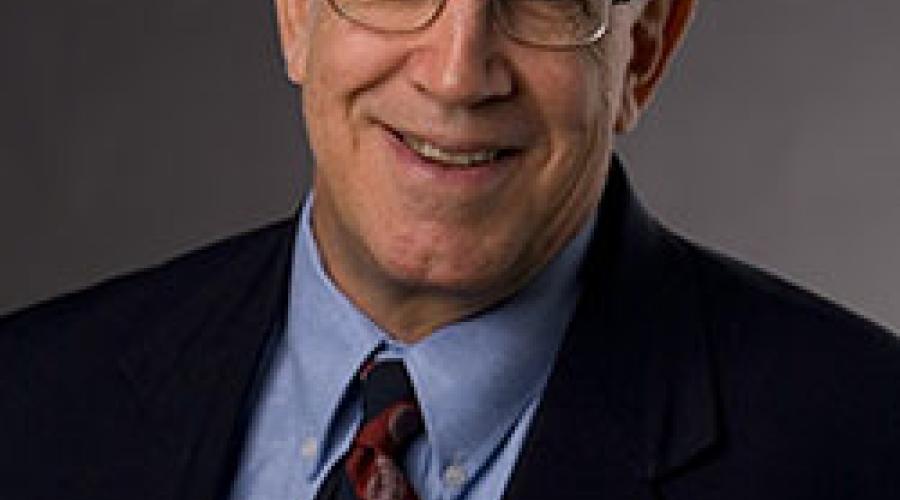

When the national spotlight shines on higher education, many turn to Professor Ronald G. Ehrenberg for insight.

For decades, the economist who is Cornell's Irving M. Ives Professor and a Stephen H. Weiss Presidential Fellow has been researching what goes on behind the scenes in American colleges and universities.

Fifteen years ago, he founded the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute (CHERI), which vets issues such as the escalating costs of a public higher education and resource allocation decisions of higher education institutions.

In an interview this fall, Ehrenberg discussed higher education issues and why he devotes much of his research to them.

Do you think President Obama's proposal to rank colleges by financial factors such as graduates' income levels is a good way to inform students about college choices?

When you're looking at graduates' income to determine ranking, you have to be careful. You don't want a university to be penalized because its graduates become teachers, social workers, join the Peace Corps, or do other things that we consider socially valuable, but that are paid only modest amounts.

The notion of coming up with performance metrics, and somehow tying it to the amount of financial aid you give students, is fraught with difficulties and may wind up penalizing the students who need the help the most.

Should young people be encouraged to go to college, even as middle-class jobs seem to be disappearing?

Yes. The income that college graduates earn is so much greater than the earnings of high school graduates, and the probability of being unemployed for college graduates is so much lower, that it pays off in the long run.

There are good jobs out there. But a job is more than earnings—it's a career, over a lifetime. The question is really, what will bring you happiness in life?

This year, CHERI celebrates its fifteenth anniversary and you mark 15 years as its director. Why did you start CHERI?

I did so with three objectives in mind. First, I wanted to be involved with the mass media, to help people understand what the economics of higher education is about. Second, I realized that you can't always do a lot of research yourself—by bringing people together, you can do much more. Third, I wanted to have resources so that I could involve both graduate and undergraduate students in research. CHERI was a vehicle that permitted me to do all of these things.

Was there a precipitating event that led you to get involved in issues of higher education?

In 1977-78, when I came up for promotion to full professor, three trustees tried to block my promotion because of testimony I had given in a regulatory proceeding. President Frank Rhodes, who had just arrived at Cornell and had never met me, very politely said to the trustees that academic decisions are best left to academics -- a position that Cornell trustees have repeatedly reaffirmed since then. I was so proud that Frank would stick his neck out for a faculty member that, after that, I would do almost anything to help him and Cornell prosper. That's how I got involved with the faculty financial policies committee and this led me to research higher education issues, to teach classes on the subject, to become a Cornell vice president and, ultimately, to serve on the Cornell Board of Trustees.

How did you get involved with the SUNY Board of Trustees?

One of Cornell's government relations people mentioned my name to the staff of Governor Paterson when they were looking for trustees, citing my expertise on the economics of public higher education and my experiences as a Cornell vice president and trustee. He sent the governor's office a number of things that I had written and, after an interview with the Governor's appointment secretary and letters of support being sent by a number of Cornell trustees, I was nominated for the SUNY board and later confirmed by the New York State Senate.

What motivates you to serve on the board?

My wife and I are both proud graduates of SUNY's Harpur College, now the liberal arts college of Binghamton University. Back in the 1960s, it aspired to be, and was, a "public Swarthmore." So, we both know firsthand what high quality public higher education can mean to a student. While we have endowed scholarships in our parents' and son's names to help support students at Binghamton, being a trustee of SUNY both informs me about the issues that public higher education is facing and allows me to use my professional expertise to further "pay back" SUNY for the wonderful education we received at Harpur.

Currently, I spend almost the equivalent of 30 unpaid days a year as a trustee working on behalf of the SUNY system and my goal is to try to see that today's SUNY students have access to the same high quality public higher education that my wife and I had as students.

Seventy to 80 percent of American college students are educated at public institutions. So, what goes on in public higher education is vitally important for our nation's future.

What would your advice be to students contemplating where to go to college?

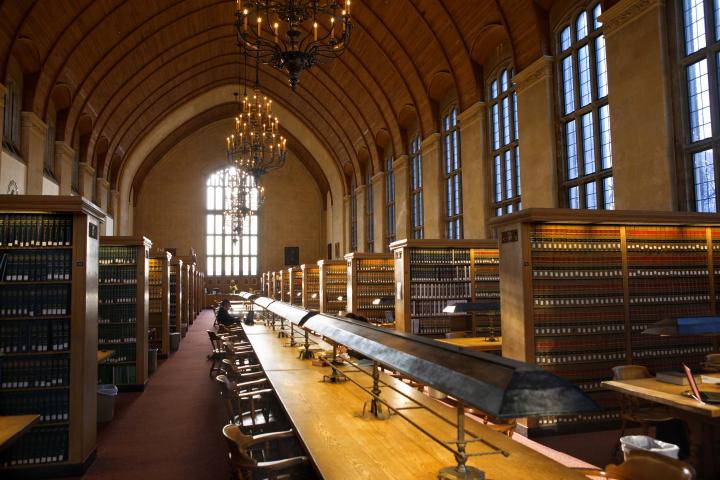

College is much more than a financial investment. It can be a transformational experience that opens up possibilities for students, teaches them to think critically and to be lifelong learners, and helps them develop philosophies of what a meaningful life and career should be.

Which college is best for any individual is based entirely on the student's academic and nonacademic interests and preferences for different types of environment -- large or small institutions, urban or rural, region of the country. Students and their families also need to understand that, especially at private institutions, there is a lot of grant aid out there. So, don't be focused on the high stated tuition levels of some expensive privates; apply to a variety of institutions that seem right for you, and when you know the ones that have accepted you and their costs, after aid, make an informed judgment.