Relentless Advocate Bridges Research, Policy and Practice

In South Korea, Taiwan, China, Saudi Arabia, India, Australia and numerous European countries, Susanne Bruyère has spoken to rooms full of disability researchers and policymakers.

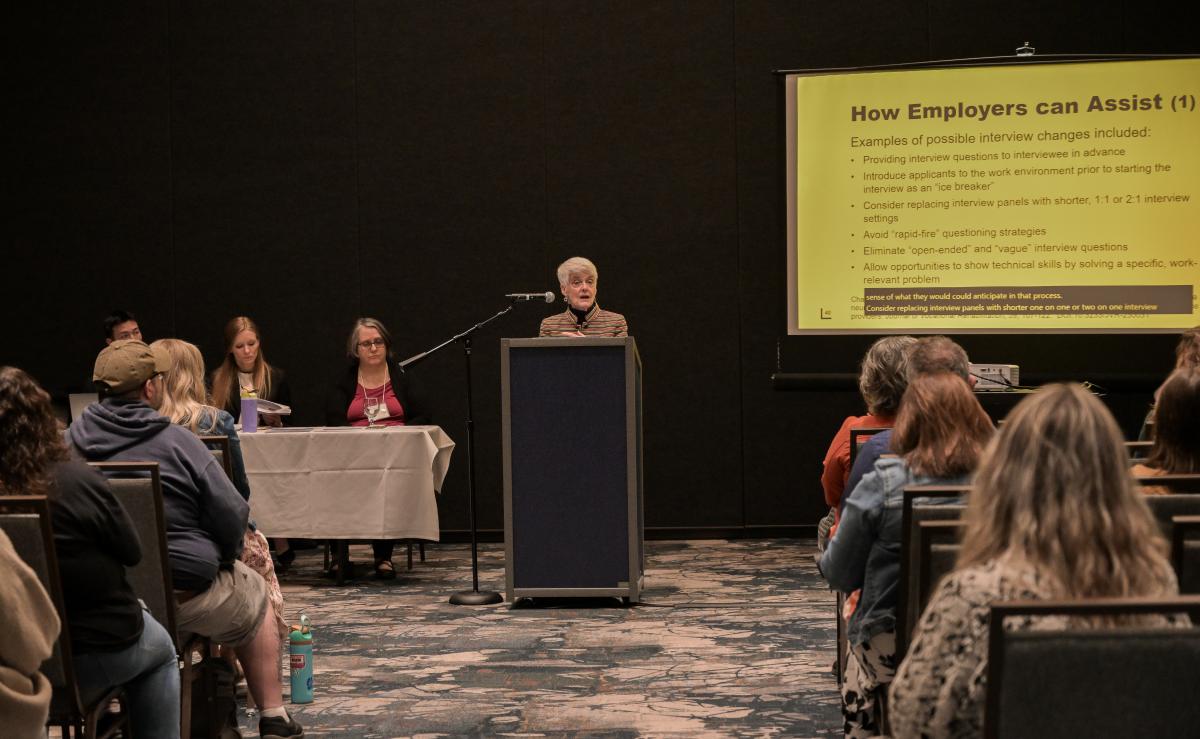

As the academic director of the ILR School’s Yang-Tan Institute on Employment and Disability, she has shared her expertise for decades both nationally and internationally.

Colleagues say Bruyère’s role in advancing disability inclusion in the workplace is indisputable.

“She has influenced how practitioners, organizations and policymakers conceptualize disability, not as a deficit, but as an essential dimension of human diversity,” says Connie Sung, the Annmarie Hawkins Research Professor in Disability Justice at the University of Michigan. “Her leadership has inspired a more holistic understanding of inclusion in the workplace, emphasizing equity, accessibility and belonging as integral to organizational excellence.”

“Susanne has a rare ability to convene and galvanize diverse stakeholders, including researchers, self-advocates, service providers and policymakers, and sustain those networks long after a project ends. Her influence extends not only through published scholarship, but also through the communities she builds, the norms she helps shift, and the institutional infrastructures she helps strengthen.”

Bruyère’s influence and community building are essential as the challenges of disability inclusion are staggering. According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 1.3 billion people worldwide, 16% of the global population, experience significant disability. In the U.S., approximately one in five people has a disability, and among working-age Americans, approximately half of those with disabilities are participating in the workforce compared to their nondisabled peers. This represents a significant loss of talent to the American workforce.

An intimate early education

Bruyère’s road to advocacy for people with disabilities, and for educating colleagues and students interested in disability inclusion, began in her hometown of Ogdensburg, a northern New York state community of 12,000 people located across the St. Lawrence River from Canada.

She was 16 years old when her father handed her an application to work at the St. Lawrence Psychiatric Center in their city, saying, “Here’s what you’re going to do this summer.”

“It was a real education for me, Bruyère recalls. “These are people who are significantly mentally ill, and I was a psychiatric attendant, which meant I would help them to get medications and walk them to different services they needed. Many were psychotic, schizophrenic. If you ever saw ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’, it was that kind of setting, although the people who worked there were nice.”

Her father worked at the hospital as an engineer, so she had visited him there many times.

“It didn’t feel foreign; it didn’t feel scary. It was a part of my growing-up environment.”

Closer to home, Bruyère’s mother suffered from postpartum psychosis when her youngest son was born; she was admitted for short-term treatment at the center.

“It was a real education about being able to know people,” Bruyère says. “You see their fragility, but you also see their strengths, and how they're struggling with brain anomalies or emotional anomalies. There's just a core of humanity that’s there to be sensitive to, to be aware of.”

Bruyère was a serious student. “I had a great role model in my father. He would always be studying through correspondence courses to progress his certification as an engineer because he hadn’t gone to college. He’d be sent huge stacks of books by mail. I had a great role model in him.”

Valedictorian of her class, Bruyère thought she would study English or psychology. Her father was adamant, though, about what she would pursue at D’Youville College, where she had won a scholarship. “He said, ‘You’re going to study special education. We have someone in our family with special needs and we need information.’ So, I did.”

Bruyère combined it with a major in psychology and graduated with a teaching certificate and knowledge to help her family guide the education of James, the youngest of Bruyère’s three younger brothers, who has Down syndrome.

Institute’s work enhanced by ILR’s broader workplace expertise

Bruyère’s undergraduate experience led to four graduate degrees at the University of California, Seattle University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she received a doctorate in rehabilitation counseling psychology.

After serving on the Seattle faculty, Bruyère joined ILR, where she has been a director of the employment and disability institute since 1990.

Bruyère and colleagues built on two decades of work by Professor William Wasmuth and other ILR researchers whose projects, dating to the 1960s, included policy and practices around independent living and employment training for people with disabilities, with a focus on improving providers’ delivery of services to people with disabilities.

Bruyère has secured over $60 million in grant funding and has served as the principal investigator or director on dozens of research projects, including a number funded by the U.S. Labor, Education and Health and Human Services departments. Most of the projects include numerous states and partner agencies.

Today, a team of 62 at the Yang-Tan Institute manages up to two dozen concurrent federal and state projects annually that include helping individuals attain and sustain meaningful employment, engaging employers in advancing equal opportunities and creating inclusive workplaces, helping people better understand their state and federal disability benefits, and helping teens with disabilities transition from school to work. The Northeast ADA Center is also housed within the institute.

The passage in 1990 of the Americans with Disabilities Act gave the institute leverage to broaden its work, Bruyère says. “We kept working with the service providers, but we started on a trajectory that was very much focused on workplace policies and practices. The ADA afforded us funding and a focus and mission to do that, which really sat right at the heart of what the ILR School is all about. This put us right on the path of using the ILR School’s expertise across the board.”

Global Labor and Law, Human Resource Studies, and other ILR departments help shape the institute’s approaches, Bruyère says, and cross-Cornell collaborations, such as partnerships with the Cornell Tech campus, have further strengthened the work.

Elevating colleagues and the prospect of workplace inclusion

Michael Murray, senior accessibility strategist for the U.S. Government Accountability Office, says Bruyère’s commitment to mentorship has played a crucial role in shaping the next generation of leaders in disability inclusion.

“I have repeatedly seen her elevate others by inviting them to speaking engagements, leadership roles and new projects. She never seeks the spotlight for herself but always works to highlight and support those around her. Susanne pairs a warm, supportive personal touch with an outstanding level of professional drive. Her contributions have been nothing short of amazing.

“Perhaps Susanne’s most significant achievement is making disability inclusion in the workplace a mainstream, strategic issue,” Murray continues. “She has elevated the conversation from compliance to one focused on talent and business strategy. When we began working together, people with disabilities were always an afterthought at DEI and HR compliance conferences. She is among a short list of leaders in the disability community who have brought issues of workplace disability inclusion to the forefront of employers’ inclusion efforts.”

Professor Michelle Meade, director of the University of Michigan Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center and co-director of the University of Michigan Center for Disability Health and Wellness calls Bruyère a “luminary” in the field.

“This is a woman who does her professional services, who contributes to the field, who is part of everything,” Meade says. “She isn’t ‘look at me, I need to be in charge,’ she lifts up other people, makes sure people and organizations have the support and service they need. She takes the time. You don’t always get that.

“She’s thinking broadly – how do we advance the science, how do we do the work that’s needed to make the changes. She translates the research into practical outputs and takes the time to put it into policy and engages corporations. She is able to put the research and data together to develop systems.”

Through that approach, Bruyère has been a pioneer in learning from companies’ efforts at designing and implementing affirmative hiring programs for neurodivergent job seekers and sharing that information with neurodivergent students and other businesses alike. Bruyère combined research and data to help businesses make the case for developing systems to hire and support people for whom neurodiversity, such as autism, can thwart their careers before they even start.

“She created a bridge into the business space to share her understanding of what business communities need and want, and the challenges individuals face, and created something solid to make a path forward,” Meade says.

Building resilience, transcending disappointment

Disability research is almost always funded by grants. When proposals aren’t funded, Bruyère is reassuring, reminding teams that “this is normal, you don’t have to get everything you go for,” Meade says.

Bruyère says she has learned to see barriers not as blockers, but as leverage for another way forward. Being part of the ILR School helps. “Being in a college that studies the workplace has been incredibly useful. If you want to do something in employment, you couldn’t have a better context than ILR to add credibility to what you do. It gives me a current strategic advantage. It helps me to be much more resilient.”

“I have a very long view and see that challenges can be advantageous. You have to look for ways to turn what may appear to be a barrier into something you can leverage. And I think we’ve done that over the years.”

Disruptions such as the defunding of a National Science Foundation project in May are taken in stride. “We look for ways to use our talents and resources in different ways. I’ve seen that work over so many situations that seem really impossible at first.”

Bruyère sets the gold standard, colleagues say, for unflagging endurance in a sometimes-discouraging landscape. Bruyère attributes her ability to push through barriers to “enthusiasm for the work. I just am so passionate about it. It just feels so worthwhile. It keeps me energized and inspires me and makes me want to get into the office and dig in every day.

“It really is very compelling work – disability touches everybody. It feels really rewarding and inspiring.”

Bruyère says one of her most memorable projects was working with 13 disability leaders from the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland in the 1990s. They visited ILR for a three-week disability leadership training to bring cohesion to disability issues across political interests.

Half of the group members were Catholic and half were Protestant, and their disabilities ranged from intellectual disability to multiple sclerosis to blindness. “We saw them go from obvious tensions across the table to a real coalescence of interests and supporting each other. People started going to each other's churches. People with cognitive impairments were pushing people in wheelchairs. They were supporting each other in all kinds of different ways,” Bruyère says.

“So, we really saw how immersion of people in a common interest could help them to transcend political divisions that didn't serve disability advocacy. It was a very powerful representation of how what we were learning could be translated to other settings.”

Mentoring the next generation of disability advocates

In addition to helping companies learn about the value of hiring people with disabilities, Bruyère creates credit internships for Cornell students, many of which have been focused on workplace and community disability and neurodiversity inclusion initiatives at corporations and nonprofit organizations in the U.S. and in countries such as South Africa, India, Israel and Australia.

Many of the students connect with Bruyère through disability courses she teaches at ILR. Bruyère and colleagues teach 11 courses through ILR’s Disability Studies Sequence, which was established approximately 15 years ago. As many as 350 students take the courses each year. Some go on to positions where they help execute their organizations’ disability inclusion practices or drive policy that supports inclusion.

Alex Eshelman ’22 was a senior at ILR when he met Bruyère, who had created an ILR credit internship at Open Doors and was his adviser. An arts collective based at a nursing home on Roosevelt Island in New York City, the organization mainly serves survivors of gun violence.

Eshelman said he was overwhelmed when he started the internship. Work was coming in from multiple bosses on multiple initiatives. Bruyère helped him establish boundaries and express his concerns to supervisors.

She also modeled how to communicate effectively in day-to-day situations.

“She’ll reply late at night, she’ll reply early in the morning,” Eshelman says. She shows you what the standard is. You kind of see how to do a good job. You can pick up a lot of game – it’s a reminder to do things well.

In Ithaca for a friend’s art show earlier this fall, Eshelman, now associate director of Open Doors, made sure to stop by Bruyère’s office. They talked music, mostly, and Eshelman was reminded of something Bruyère taught him about momentum – “the more you do good work, the more you can do good work.”

Eunkytoung “Sophie” Shin, a professor in the Department of Social Welfare at Dankook University in South Korea, was a visiting scholar in 2024 at the Yang-Tan Institute. Bruyère advised her as she investigated how the swift adaptation to digitization and AI has increasingly isolated workers with disabilities.

“The idea that social structures must change and that employment practices need to be transformed has often come to be viewed as unrealistic,” Shin says. “However, through Susanne and the research and publications emerging from the Yang-Tan Institute, I came to realize that it is indeed possible to change the employment environment for people with disabilities by building networks across the public and private sectors, promoting interdisciplinary approaches, and fostering collaboration among diverse professionals. This gave me the conviction that Korea, too, must seek ways to promote such networks and collaborations.”

When Shin completed her study at ILR, she gave Bruyère an excerpt in calligraphy from the “I Ching,” an ancient Chinese classic that translates to “Book of Changes.”

“It is often cited to highlight the importance of leadership, character and inclusiveness in fostering harmony. I felt it perfectly reflected Susanne’s character.”