Healthcare Insights by John August

Eliminating Injustice in Healthcare

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed many failures, inequities, and broken systems. Though profound inequality is a recognized truth about American society, like so many “Inconvenient Truths” (the title of former Vice President Al Gore’s Oscar Winning Documentary film on climate change) inequality lingers in our consciousness, but in some ways, like climate change, seems too daunting to know what to do.

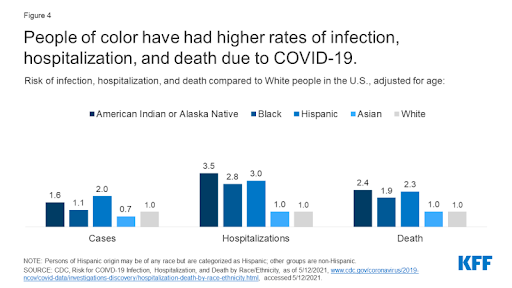

One of the great inequities in our nation is known as disparities in health and healthcare. We have witnessed how the COVID-19 pandemic took larger death and illness tolls in communities of color and communities of poor socio-economic status.

In the graphic below, the stark disparities from the impact of COVID-19 are clear:

These inequities that have come to light during the pandemic are not new:

“The disparate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing incidents of police brutality, and recent rise in Asian hate crimes have brought health and health care disparities into sharper focus among the media and public. However, health and health care disparities are not new. They have been documented for decades and reflect longstanding structural and systemic inequities rooted in racism and discrimination. Addressing these inequities could help to mitigate the disparate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and prevent further widening of health disparities going forward. Moreover, narrowing health disparities is key to improving our nation’s overall health and reducing unnecessary health care costs.” (“Disparities in Health and Health Care: 5 Key Questions and Answers”, Nambi Ndugga and Samantha Artiga, Kaiser Family Foundation, May 11, 2021)

To clarify the root causes of disparities in health and health care, please watch this brief video:

A Tale of Two Zip Codes - YouTube

We have also known for a very long time that our health is determined largely by factors outside of the healthcare system itself as shown in the graphic below:

On a macro scale when we discuss disparities in health and healthcare, it is clear that only 20% of the causes rest in the health care system itself. 80% of the determinants of disparities are rooted in socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and the physical environment in which people live.

So it would seem that the broad overview of facts and figures, the Inconvenient Truths about perhaps the most fundamental measure of quality of life, one’s health and life expectancy, are daunting and seem out of reach to impact successfully.

One of the great challenges of our time is how to confront and succeed at making positive change in the profound challenges of climate change, inequality, and social peace and well-being

In my work, I think of the millions of people who go to work each day in health and healthcare related fields: from primary care doctors to home health care workers, from policy makers and government officials to medical assistants who greet patients when they come in for a clinic visit, and to nutritionists who work in public schools, among others.

What I see is practical opportunity to reduce the disparities in health and healthcare. Such practical opportunities exist everywhere, as we can see in this powerful video about breast cancer screening and prevention among Hispanic women in the Pacific Northwest. Please watch it:

The Latina Initiative: Reducing Disparities in Breast Cancer Screening - Bing video

What is so powerful and practical about this story is that it was conceived as a true community effort which includes public education and awareness, direct reach out to vulnerable women, coordination of care, and high quality clinical treatment. Central to the program is coordination among community leaders, healthcare executives, managers, and frontline workers.

It is a story driven by Kaiser Permanente (KP) in Oregon. KP is often thought of as a model for healthcare for the nation due to its unique model of integration of insurance, medical care, and ownership of its facilities. Its core principles include:

- Prevention as the core strategy

- Large multi-specialty medical groups

- Research to continuously find and implement best practices and evidence based medicine

- Fully integrated electronic medical records

- Labor-Management Partnership

The frontline participants in this program are part of the national vision of Kaiser Permanente, connected through the Labor-Management Partnership.

Across the KP system, the frontline staff, numbering some 120,000 union members, 20,000 managers, and 20,000 doctors co-exist in the largest single health system in the nation. It is the best opportunity that I can think of to show the way for the re-organization of healthcare which requires continuous improvement. Health disparities represents one of the biggest seemingly intangible sources of inequality in our nation, but through planning and collaboration, stories like the one in the video on breast cancer screening and prevention could and should expand exponentially.

We should be inspired by these successes of leadership, organization, and broad participation!

One of the most powerful experiences I had when I co-led the Labor Management Partnership at Kaiser Permanente on behalf of labor was my learning and observation about a highly successful program called Pro-Active Office Encounter (POE). This initiative asked medical assistants (all union members) to add important duties to their already busy days of checking in patients for visits, working through billing and insurance questions, and assigning patients in proper order for their appointments.

It was in the KP clinics in Baldwin Park, a community in Southern California which has as a population that is nearly 60% people of color according to the 2019 census that is another great example of how research, leadership and frontline engagement made a huge difference in reducing disparities in healthcare.

Baldwin Park was an area where POE was first developed. It expanded across the region to the more than 3 million patients in the Kaiser Region.

When the program was introduced, the medical assistants were less than enthusiastic as their days were already very busy. They were being asked to learn new computer skills, to look at patients’ records to determine if they were behind on preventive screenings, and to look for biometric values (blood pressure, sugars, cholesterol, and whether or not the patient was a smoker).

The patients who were coming for their visits were generally there for routine issues and not looking to be told they needed a screening or that they had a problem they were not expecting to hear about. The medical assistants were concerned about how to communicate with the patients about highly personal issues they were not prepared to hear about.

However, due to the collaborative environment of the Partnership and having access to time and educational opportunity built into the union contract, medical assistants learned the new skills and began to experiment about how they could work together to ease some of the additional duties.

Most importantly, they learned of the benefits of catching missed opportunities for breast cancer screening, colo-rectal screening, prostate cancer screening or other anomalies in health conditions. They learned how early detection of serious disease, and updates on health biometrics that can lead to serious chronic conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol can be prevented! They learned about the benefit to the patients and about how these preventive measures saved precious dollars by preventing expensive preventable procedures.

The medical assistants learned how to make appointments for the patients right then and there without having to wait for additional phone calls and messages.

As one of the medical assistants remarked after embarking on the POE program:

“Communication has improved, we say ‘my patients’, not just ‘the doctor’s patients’…POE brought us closer together.”—Marisela Guevara, Medical Assistant.

I had the opportunity to interview medical assistants about their experience, and among the most common things I heard was, “after 25 years of sitting behind a desk, I never imagined I could learn so much and help our patients in ways I never imagined.”

And some of the outcomes achieved:

Along with other concurrent improvement initiatives, POE has contributed to a 27% increase in colon cancer screenings, a 12% increase in breast cancer screening, and an 18% improvement in cholesterol control region-wide.

When we are reminded of the demographics cited above, with a community which is 60% non-white, we see how disparities in healthcare can be significantly reduced. The achievement was accomplished by employing new practices to all patients, based on a commitment to continuous quality improvement.

The learning experience among the clinic staff is also central to the program: the commitment to learning these new skills brought many frontline healthcare workers into the world of elimination of health disparities in profound ways that they otherwise would likely never have been able to.

(The information for the Baldwin Park POE initiative comes from: “Kaiser Permanente Baldwin Park Medical Center— Information Technology Propels Expansion of Medical Assistant Role” by Lisel Blash, Susan Chapman, and Catherine Dower, Center for the Health Professions at UCSF © November 2010, Revised November 2011)

Finally, many health systems around the country are making major strides in the permanent integration of equity issues into the daily activity of quality improvement. And this is one of the most important elements to understand of what it takes to eliminate these disparities.

On the one hand, it is clear that the long-range elimination of health disparities is tied to long-term economic, social, and political transformation to eliminate the root causes of racism and poverty. The same long-range transformations are necessary for the elimination of the causes of climate change and to make our society secure and peaceful for all.

We do not know how long such fundamental transformation will take, nor do we expect it to be a linear success, even though we know with each day, the challenges accelerate and become even more complex to solve.

How we engage one another, how people learn to participate in change is as important as the major public policy shifts .This is the nature of citizenship, and as individuals learn to participate in change that is positive two outcomes are likely: change does take place at the local level which is an unequivocal good, and the people who participate in the change feel that they have made an important contribution.

The following strategic work at the nations’ largest public health system illustrates the practical implementation of the theory and practice of elimination of disparities at the frontlines of care.

The Institute of Healthcare Improvement has shared with us the experience and contributions to the elimination of health disparities from New York City Health+Hospitals. (from the IHI.org website). It should be noted that the workforce at NYC Health+Hospitals is 100% unionized.

“The daily work of performance improvement occurs at the frontlines of care. Included here is a description of work that shows that when addressing equity and inclusion, there are many things to be said and done. But all too often much more is said than done. To help prevent this, we highlight a purposeful, iterative, and lasting strategy that health systems can use to fundamentally advance their equity agenda.

NYC Health + Hospitals (NYC H+H) is the largest integrated municipal health care system in the United States, serving over 1 million patients annually. As a safety net system, tackling systemic injustice such as structural racism has always been central to our mission. In New York City, we have the privilege of serving a diverse patient population where nearly 3 million New Yorkers were born outside of the US. Of NYC H+H’s registered patients, less than 9 percent racially self-identify as White non-Hispanic.

COVID-19’s disparate health effects among racial and ethnic groups and the recent civil unrest following the brutal killings of George Floyd and many others have helped our nation focus on health and racial inequities as never before. Given the gravitas of this work and our experience, we propose a comprehensive 4-step strategy that health systems can utilize to ingrain equity into quality and safety work:

- Conduct a departmental needs assessment. To deliver on the promise to improve health care quality for all, a health system must first review the equity knowledge and needs of its workforce because quality and safety are inextricably linked. Similar to work done by some public health departments, like the Hartford Department of Health and Human Services through their Health Equity Action Training (HEAT) project, it’s important to begin with a needs assessment conversation with system-wide Quality & Safety (Q & S) leaders to ascertain current state.

Ideally in-person, such discussions familiarize staff with standard definitions of subjects like equity, justice, racism, and health disparities and establish a baseline of knowledge. More importantly, these sessions should create a psychologically safe and brave space to discuss difficult topics that have often been considered taboo in the workplace setting. In partnership with the Office of Diversity + Inclusion (D + I) or Human Resources (HR), this needs assessment should be extended to listen to employees across the health system.

Professionally facilitated, digital town halls allow for anonymous participation in real-time polls and free-text responses during the sessions. We suggest sampling at least 5 percent of the total workforce, with diverse representation from every service line within the enterprise. This purposeful cultural shift, education, and analysis allows more data-informed, rather than emotionally reactive, next steps.

- Focus on departmental work stream mapping and capacity building. To assess current work structures, complete a departmental organizational chart. Every division working on quality and safety should share their current work streams and identify areas for opportunities to make their work more equitable. Consider creating a survey to collect anonymous self-reported data on race, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, gender identity, country of origin, age, religion, disability, and zip code (this data is known by the acronym REaL SOGI) to assess the current demographic makeup of your office. Quality & Safety departments should partner with HR and D + I and ensure their recruitment, retention, and promotion practices are aligned with the system’s equitable hiring strategies. This information can lead to the creation of an equity dashboard like the one the municipal government of New York City uses to display its diversity data to increase transparency and accountability.

To ensure sustainability of this cultural shift, health systems should consider further capacity building with the development of a Director of Equity, Quality & Safety leadership role. Modeled after the equity leadership position within the Quality & Safety team at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the person in this role helps to guarantee that equity and inclusion principles are explicitly represented and fundamentally ingrained into the core of all Q & S initiatives. The Director of Equity, Quality & Safety can also help the Office of D + me or HR set up a diverse Equity and Access Council to be the governing body for equity, diversity, and inclusion initiatives within the organization. By leveraging existing departmental structures, like those utilized at health systems such as Northwell Health’s Center for Diversity, Inclusion and Health Equity, organizations can identify where equity initiatives can be woven into key daily functions, and the structure through which they are analyzed.

- Apply equity lenses to key existing Q & S work streams through iterative PDSA (Plan-Do Study-Act) cycles. Strategic priorities for core quality and safety functions will be identified through the needs assessment and departmental workflow mapping. For example, re-envisioning the Root-Cause Analysis (RCA) process through an equity lens can more effectively identify inequities and bias. A standardized toolkit, which encourages investigators to analyze contributing factors at the interpersonal (explicit bias), human behavioral (implicit bias), institutional (policies and practices), and structural (societal determinants of health) levels, helps to ingrain equity into this process.

A second method is the inclusion of mandatory bias “triggering” questions into the real-time incident reporting system, including a drop-down list of qualitative contributing factors for reporters to choose from. These will address potential underlying causes of bias that led to the adverse patient safety event. If the triggering question is answered either yes or no—depending on the prompt—or bias is listed as a contributing factor, risk managers should address bias-related concerns explicitly in their investigations. This will allow frontline staff to identify and easily report equity-related concerns for further elucidation by Patient Safety and Risk Management teams. The number of RCAs conducted with equity- or bias-related concerns, as well as incident reports that trigger positive for potential bias, should be collected and analyzed.

Performance improvement (PI) teams, who often implement and monitor system-wide quality improvement (QI) projects, can also ingrain equity into their activities. The UCSF Center for Health Professionals’ use of a disparities lens for QI, includes tenets of selecting diverse multidisciplinary teams and should inform a system-wide PI charter. A system’s PI goals should include a focus on equity and access. During needs assessment, it may surface that current patient-reported REaL SOGI data collection practices need revision to ensure accuracy and completeness process to improve the system-wide collection and validation of self-reported REaL SOGI data in the electronic health record through iterative PDSA cycles is crucial to informing this work. This stratified high-fidelity REaL SOGI data will help PI teams identify and improve identified health disparities and inequities.

- Use data visualization with transparent milestones and measures. Systems should track the impact of their equity and inclusion strategy on Q & S work over time. These metrics should be established early and include tiered process and outcome measures at the patient, facility, and system levels. These metrics should be updated and refined as the health system’s approach matures. Examples of initial measures include percentage of patients in the patient self-reported REaL SOGI data who choose “Other” or “Prefer to not disclose,” the number of RCAs conducted during which equity- or bias-related concerns were discussed, and the percentage of PI projects presented to the board that look for differences using REaL SOGI stratified data. Available on an equity Q & S dashboard, these metrics should be reported back to staff at regular intervals.

Together, we need to not only reimagine change, but take purposeful action to ingrain equity into every facet of quality and safety.”

Every hospital in the country maintains scorecards on key quality and patient experience measures. Everything from hospital acquired infections, readmissions, falls and trauma, to nurse/patient communication, to quietness on the ward, to care coordination, to doctor/patient communication, and more are publicly recorded measures of quality, safety, and patient experience.

Today all of these measures can and should be dissected through the prisms of race and ethnicity. We know from experience that the disparities we see on the macro scale are reflected at the unit level in every hospital in the country. For every measure, there are glaring disparities in outcomes for people of color and people of low socio-economic means.

Teams of doctors, nurses, technicians, aides, and Environmental Services (EVS) staff can contribute to the elimination of disparities in health every day. These tragic failures must not remain high level abstractions of Inconvenient Truths. On every unit of every hospital, collaborative, data driven work can create the opportunity for action and learning as shown in the examples in this article.

Instead of health disparities remaining an Inconvenient Truth they can become an engine of learning, commitment, and justice in the daily lives of the people who provide care and who are members of the community they serve.

I think of this as citizenship in the workplace…citizenship as participation and contribution and purpose.

About the Author: John August is the Director of Healthcare and Partner Programs at the Scheinman Institute.