September 2020 Job Disruptions Update: Dimmer Prospects for a Speedy Rebound

The September 2020 Bureau of Labor Statistics’ jobs report (that is, the Employment Situation news release ) shows that from mid-August to mid-September, U.S. labor market conditions improved [more slowly than in the past four months]. A later post will examine differences by gender and race.

A post in March explained why the jobs reports are so influential and what indicators I track to understand the impact of COVID-19. Also, see updates for April, May, June and August.

-

Data quality is good. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported no new data collection or quality issues (see the bureau’s accompanying statement ). Pandemic-related disruptions lowered response rates for the household and payroll surveys (see questions 1 and 3 of the statement , respectively), but they are still high enough to meet the bureau’s standards.

-

The labor market slump is still very deep; the rebound is clearly slowing.

-

Payroll jobs increased by 661,000 in August, about three percent of the 22.1 million jobs lost in March and April, less than half of August’s gain of 1.4 million jobs. As of September, about half of the pandemic’s job losses have been regained.

-

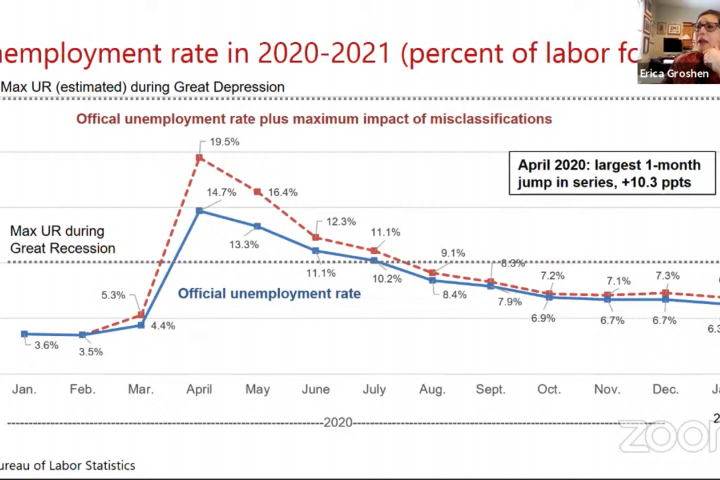

The official unemployment rate declined to 7.9 percent. The bureau estimates that had there been no misclassification, the official unemployment rate might have been as high as 8.3 percent. See questions 5-9 of the statement and my previous discussion about misclassification.

-

The labor force participation rate fell by 0.3 percentage point in September to 61.4 percent. This large exit of workers from the labor force is disturbing news: more than twice as many people left the labor force (695,000 t) as those who got new jobs (275,000). These exits are concentrated among women, likely reflecting high job losses in the service sector as well as disruptions in child care and in-person schooling.

-

The employment-to-population ratio was essentially flat at 55.6 percent and remains far below February’s ratio of 61.1.

-

The labor underutilization rate “U6” declined to 12.8 percent, still much higher than February’s rate of 7.0 percent. U6, the agency’s broadest measure of labor underutilization, counts as underutilized all workers who are unemployed or working part-time involuntarily, plus those who have left the labor force, but still want a job and have looked for one or worked during the past 12 months.

-

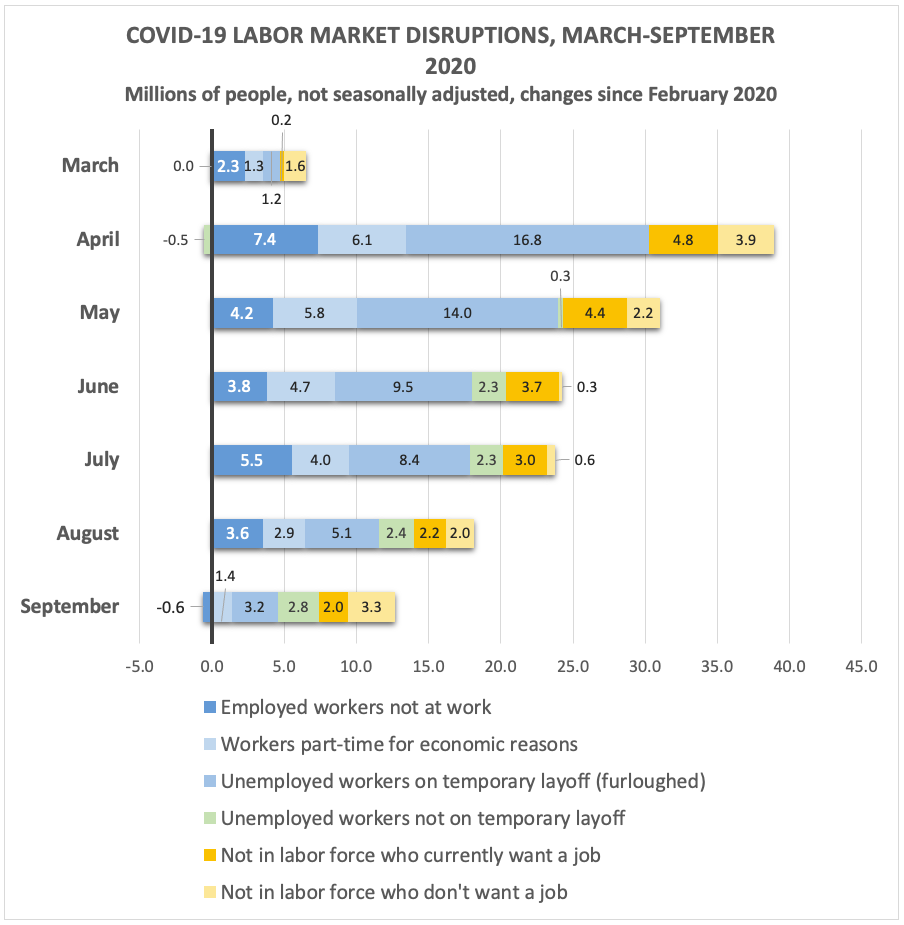

My COVID-19 disruption table (below) adds up six distinct ways the crisis has disrupted (suspended or curtailed) the jobs in the U.S. labor market. Since disruptions can take many forms, I track these indicators:

-

Employed workers not at work—workers on leave from their employer, paid or not

-

Workers part-time for economic reasons—workers who prefer to work full-time but only found a part-time job or who usually work full-time but had hours reduced by their employer

-

Unemployed workers on temporary layoff (furloughed)—laid-off workers who expect a recall

-

Unemployed workers not on temporary layoff—workers permanently laid off, new and re-entrants and job leavers

-

People out of the labor force who currently want a job—people without a job, not looking for work, but say they want a job

-

People out of the labor force who do not want a job—largely students, retirees and people with disabilities or caring for family members.

This measure of COVID-19 disruptions is the change in the number of workers in each category since February. The first three categories capture workers whose relationships with an employer are intact despite disruptions, in contrast to the latter three. See here for why that matters. (Note: I use seasonally unadjusted data, for comparability.)

-

-

September changes. Although the headline numbers in the jobs report showed improvement in September (that is, payroll jobs rose and the unemployment rate fell), a deeper look is concerning. While my metric of the number of disrupted workers also declined (by 4.4 million from August to September--see the first two columns of the table), it suggests challenges ahead for the economic recovery.

Most notable is the “hardening” of disruptions. All three categories of disruptions that preserve ties with employers declined. This likely reflects recalling workers or increasing their hours (that is, encouraging reasons) or the conversion of temporary layoffs to permanent ones (that is, concerning reasons). Indeed, there was deterioration in two of the three categories of disruptions without ties to employers. From August to September, half a million more workers were counted as unemployed without a tie to their employer and 1.2 million more workers were out of the labor force, saying that they did not want a job.

-

Status of disruptions. Despite the previous improvements, the third and fourth columns of the table show that by mid-September, COVID-19 was still disrupting the jobs of over 12 million workers, or about seven percent of the labor force. Only six million (about half) of those workers are classified officially as unemployed. Thus, focusing solely on changes in the unemployment rate continues to understate the severity of the disruptions caused by COVID-19.

The bar chart shows how the workers in the various disruption categories have changed each month from March to September.

The good news is that the scale of disruptions has declined markedly since April, when they affected 38 million workers (23 percent of February’s labor force. However, it is concerning that fewer workers whose jobs have been disrupted are still connected to an employer. In September, just 33 percent of disrupted workers maintain such a tie (shown in the blue segments of the bars)—down from 79 percent in April.

-

-

Pulling it together

At first blush, September’s decline in the unemployment rate and increase in payroll jobs look strong. However, the numbers behind the headline indicators show that labor market conditions remain weak and prospects for a speedy recovery have dimmed. The “easiest” layoff recalls and hours restorations are likely behind us.

It is worrying that from August to September, twice as many people (especially women) left the labor force as got new jobs. Furthermore, as of September, only about a third of disrupted workers maintained relationships with employers, which is likely to slow the pace of recovery going forward. Now, in contrast to April (when only a fifth of disrupted workers were disconnected from their employers), two-thirds of the workers whose jobs are disrupted have been cut loose permanently; they are either searching for a new job or have left the labor force. As the pandemic continues, fewer jobless workers are on temporary layoff and more are permanently laid off and have left the workforce altogether.

Finally, the composition of labor force exit has shifted markedly as of September. Two-thirds of the growth in people out of the labor force since February is due to people who do not want a job. This could portend a troubling long-term decline in labor force participation due to the pandemic.

| August to September change | Continuing disruptions (February to September change) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Millions of disrupted workers | Share of change | Millions of disrupted workers | Share of disrupted workers | |

| Type of Job Disruption | ||||

| Type of Job Disruption | ||||

| Employed workers not at work | -2.5 | 57% | -0.6 | -5% |

| Workers part-time for economic reasons | -1.5 | 35% | 1.4 | 11% |

| Unemployed workers on temporary layoff (furloughed) | -1.9 | 43% | 3.2 | 27% |

| Unemployed workers not on temporary layoff | 0.5 | -10% | 2.8 | 24% |

| Not in labor force who currently want a job | -0.2 | 5% | 2.0 | 17% |

| Not in labor force who don't want a job | 1.3 | -29% | 3.3 | 27% |

| Total disrupted | -4.4 | 100% | 12.1 | 100% |

| Share of pre-COVID (February 2020) labor force (164.2 million) | -3% | 7% | ||