In the Middle

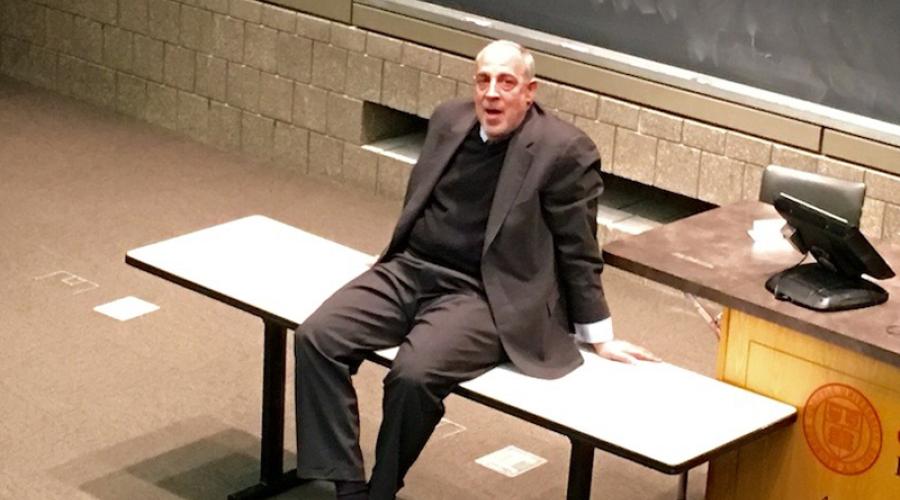

“All’s well that ends,” said Martin Scheinman ’75, MS ’76, lecturing at ILR March 20, as he described his approach to his mediation between the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association and the City of New York this winter.

Harry Katz, Jack Sheinkman Professor of Collective Bargaining, introduced Scheinman and spoke about opportunities in the recently developed Conflict Resolution Club for students developed this year by the Scheinman Institute on Conflict Resolution.

“For the club, we are going to create more activities like this where there are people involved with conflict in one form or another to come talk and meet with students of the club,”said Katz, Scheinman director. “We have research opportunities and scrimmaging opportunities within the club.”

“The PBA and the City of New York have had a very contentious relationship over the last 20 years.” Katz said.

“The union negotiates collective bargaining agreements periodically with the city, but the contentiousness has led to the phenomenon that the PBA and the city have rarely actually completed a regular negotiation. Instead, they often go to impasse.”

“The law in New York state requires if they go to impasse that they can have recourse through what is called interest arbitration when a panel of arbitrators settle their conflict dispute,” Katz said.

The police, who hadn’t had a contract since 2010, settled with the city on a new pact in January. The contract, for 23,000 officers, goes into effect March 15, includes back pay from 2012 through last year, and continues through July 2017.

Scheinman talked about the tense relationship between the police and the mayor along with his personal meetings with Mayor Bill de Blasio at Gracie Mansion.

“If you remember what happened, we had a couple of shootings in this country, Black Lives Matter was going on, and all of this in the background,” Scheinman said. “We had a very serious conversation about having to find a way that the minority community and the police can figure out, at least, to coexist.”

During the middle of the negotiations with the mayor, two police officers were killed in New York City.

“We had not started negotiations yet, and we were just talking about a format to get along because I hold a little influence since I knew the police, and their lawyer was someone we knew who actually is involved with the Scheinman Institute,” Scheinman said.

“Then, everything stops when the president of the PBA got up publicly saying that their blood is on the hands of the mayor and now everything is just a disaster.”

When the mayor came to mourn the deaths of the officers, the police turned their backs on him, Scheinman said.

“I was appalled by this, and I was not appalled by the police’s feelings,” he said. “I was appalled about how this will work out.”

The police were also angry because they felt they were mistreated by the previous arbitrator, according to Scheinman.

“The prior arbitrator was Howard Edelman, and everybody knew that he was my first assistant,” Scheinman said. “He issued a reward, which I think, on the facts, was probably correct and they went crazy.”

“They went to his home with fake coffins and talked about how people are going to die as the result of what he did,” Scheinman said.

About 40 arbitrators signed a letter saying to the Public Employment Relations Board and to the New York City Office of Collective Bargaining that they refused to ever do any work for the police.

“I had a little bit of a public position because of the Scheinman Institute, and I was thinking whether to sign on or not to sign on,” Scheinman said. “My colleagues were mad at me for not signing on, but I finally decided not to sign.”

“I believed that there might come a time that I might be able to solve this insanity, and if I already took a public position of not being involved there would be no way of going back,” Scheinman said.

There was a perception by the police that other unions were favored for better deals in the past. Scheinman outlined the course of the bargaining over the case as the police constantly compared their contract to other union’s contracts.

“We just went through the deal and made it,” Scheinman said. “The mayor and the cops had to stand up at a press conference that you can see on YouTube and talk nicely about each other and they did.”

The contract for the police went through by about 97 percent, according to Scheinman.

“Traditionally, an employer would say that is not good since that’s too much,” he said. “I think it really told you a better thing -- that people sometimes just get tired of fighting.”